New Mexico

The oil company's sign - in the middle of Jozee's garden: "High risk area"

Wolfgang Hansson

Published 17.37

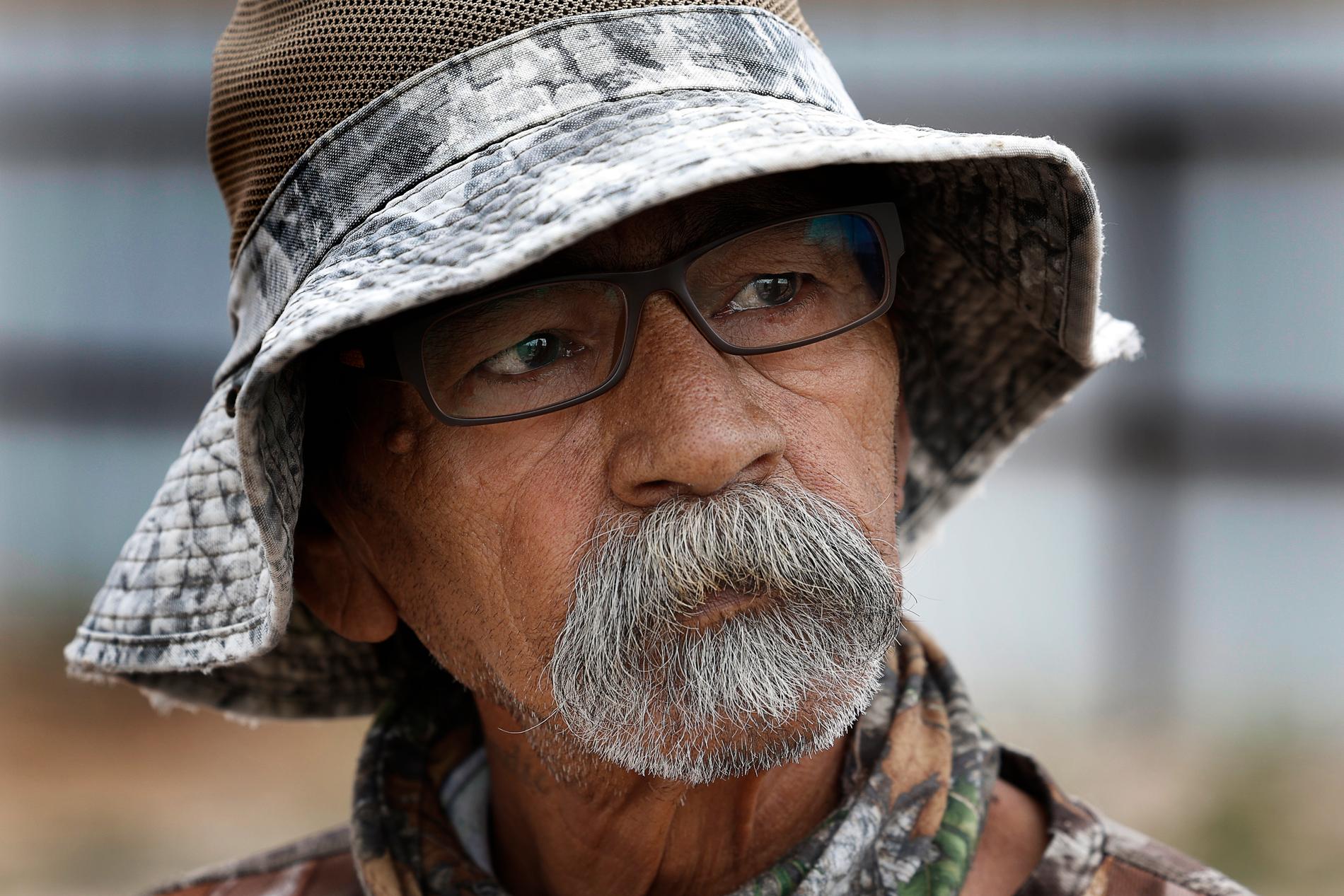

Moses Rodriguez shows a picture of how his farm was surrounded by green fields. It was a few years ago.

Today he lives in the middle of an industrial area, surrounded by gas and oil plants.

- Too devilish. They work around the clock. But there is nothing I can do to stop them.

CARLSBAD, NEW MEXICO. The picture is not even ten years old but it is like two different worlds.

The remodeling began when Moses' sister-in-law, who lived in the house next door and inherited parts of the farm, decided to sell to a local developer. He in turn leases the land to companies that work in the oil and gas industry.

- I tried to persuade her not to, but she was attracted by the money, says Moses with a helpless look. They want to buy my house too but I didn't want to move. In addition, they offered far too little pay.

Moses Rodriguez now lives next door to oil facilities. Photo: Jerker Ivarsson

Moses runs his fingers thoughtfully over his gray beard.

- Today I almost regret it. It is hell to live here and now it is almost impossible to sell the house. Who wants to live here?

The back of Moses' plot is fenced off by a two meter high fence made of corrugated iron. He steps up onto the center barrier to show what it looks like on the neighboring property where corn, hay and other crops used to be grown to feed the cattle his father had.

Today, a large number of trucks are parked on the other side and a teddy bear red tank is right next to Moses' lot. Dirty water from oil extraction is stored in it.

- The tank is leaking so water is constantly flowing into my plot, says Moses. They pump water in and out of the tank at all times of the day. I wake up at night from the noise.

He steps down from the fence and lifts away a collection of large stones that hold a meter-long piece of rusty sheet metal in place.

When he lifts the piece of sheet metal, a large sinkhole appears.

Moses goes further down the plot and lifts up a number of stones from another hole.

- There are lots of holes in the ground on my plot. I'm convinced it's due to the water leaking in.

The company on the other side has its machinery parked so that it sticks up on the other side of the fence. From inside, music is played at high volume. Machines run back and forth.

A few hundred meters away is a gas plant. A faint stench of methane and rotten eggs hangs in the air. The smell comes from leaks in the facility and from burning the gas that is a by-product when pumping up the oil.

From a special camera, we can see how it "smokes" from the gas plant.

- Heavy emissions of methane, says biologist Charlie Barrett, who operates the camera. So big that I have to report them to the authorities.

When he lifts the piece of sheet metal, a large sinkhole appears.

Moses goes further down the plot and lifts up a number of stones from another hole.

- There are lots of holes in the ground on my plot. I'm convinced it's due to the water leaking in.

The company on the other side has its machinery parked so that it sticks up on the other side of the fence. From inside, music is played at high volume. Machines run back and forth.

A few hundred meters away is a gas plant. A faint stench of methane and rotten eggs hangs in the air. The smell comes from leaks in the facility and from burning the gas that is a by-product when pumping up the oil.

From a special camera, we can see how it "smokes" from the gas plant.

- Heavy emissions of methane, says biologist Charlie Barrett, who operates the camera. So big that I have to report them to the authorities.

- Wherever the oil industry establishes itself, the land is destroyed, complains Moses.

The patchy, extremely dry lawn at the front of the house is completely empty except for an iron scaffolding from which hangs what appears to be a white lampshade. Below it hang some light blue objects that measure the air quality.

Moses Rodriguez shows on his cell phone how he receives reports on air quality. Right now it says "poor".

- Often it says "hazardous to health - go indoors and close the windows".

Although Moses is 68 years old, he still worries about his health.

- Some days it's so bad that I have to wear a face mask to put up with the smell. But I have no choice. I have to stay here.

Grandma is sick so we talk outside. It's about 20 degrees in the air but it's blowing strongly.

- When I turned 18, I started to get sick, but at first no one understood what was wrong, says Jozee, who is dressed in blue jeans and shiny black shoes.

- It took two years to get a diagnosis. Hormonal disorders. Just the kind that can be caused by the toxic substances released by the oil and gas industry.

She got so bad that she had to quit school and give up her engineering dreams.

Josee Zuniga. Photo: Jerker Ivarsson

At the back of the plot, six different oil companies have laid pipelines right across their plot.

- When the last two wanted to withdraw, we tried to talk to them. But it just said that either you write on the papers or we do it anyway. Even though it is our land, we are completely disenfranchised.

This is due to the Mineral Rights Act, which gives the companies the right to extract what is under the ground. This also includes pipelines and other infrastructure that enable the transport of what is extracted.

A white pole with a yellow painted top marks where the pipelines go. Here, the ground is completely clean of the bush vegetation that otherwise grows on the plot. A sign announces that no one is allowed to dig here without first contacting the company.

- It's our plot but we can't even dig here. A week or so ago they put up a sign "High risk area - do not cross here". It doesn't feel good to live in a place where they constantly warn of dangerous things.

She complains that they never get any information about what is going on. No one from the companies knocks on their door. No one puts any information leaflets in the mailbox.

- In recent years, we have felt more and more earthquakes due to all the drilling in the ground. It has caused cracks in the foundation of grandma's house that we have to repair.

She points to a pile of cement sacks stacked in front of the house. Earthworks have begun around the foundation.

- The companies take no responsibility and pay nothing. They treat us as waste, a kind of necessary sacrifice, instead of human beings.

The activist Kayley Shoup, who drove us here, points out that the companies donate money to roads and various activities inside Carlsbad.

- But individuals affected by their extraction receive no compensation. We have a Democratic governor who likes to market New Mexico as being at the forefront of environmental issues. But it's mostly a game for the gallery.

From where we stand, we see several flames from steel pipes where the gas is released.

On the other side of the road, a facility has just been built that appears to measure how much flows through the pipes.

A strong gust of wind causes the fine-grained sand to fly around in the air, creating an almost impenetrable cloud of dust that forces us to walk back towards the sheltered house.

- I have put my life and my dreams on hold, says Jozee Zuniga. I have to help take care of grandma. The future feels very uncertain.

Does she see any hope for it to get better?

She looks down at the ground and lightly kicks the soil with one foot.

- No, she states coldly. I am convinced that the Permian Basin, where we are located, will be the last place on earth still producing oil.

Aftonbladet's reporter Wolfgang Hansson and photographer Jerker Ivarsson on location in Carlsbad, New Mexico, USA. Photo: Jerker Ivarsson

Inga kommentarer:

Skicka en kommentar