Here is the price for your new H&M clothes

by

Staffan Lindberg and Lotte Fernvall

Every year, 100 billion new garments are manufactured in the world.

Each is worn seven times — then it is discarded.

The fashion giant H&M promises customers that they take responsibility for the environment.

But Aftonbladet can today reveal that contaminated water is pouring out of the clothing chain's "fast fashion" factories in Bangladesh.

Aftonbladet reveals: Secret emissions at H&M's clothing factories

DHAKA.

If Soma Akhter, 25, wanted to, she could predict the color of next year's fashion.

Just look down into the waste water under the bamboo stilts that support her house.

It shines in turquoise.

The water comes from the neighborhood's textile factories.

Soma Akhter herself has worked in one of them, before she lost her job during the pandemic.

She knows she will have to find sustenance there again soon.

Every evening, one hour after sunset, the dirtiest water is released.

The thing that causes the foam to stick to the grass and her neck to become swollen and stiff.

Which makes her unable to eat because the smell reminds of dead bodies.

This is a story about people and water.

About melting glaciers high up in the Himalayas, which feed the huge rivers that press down through fertile plains where people have lived and farmed for thousands of years.

It is also a story about the clothes we wear.

It can begin in an H&M store on Drottninggatan in Stockholm, where faceless mannequins in glittering sequined dresses look out at the Black Friday customers.

Or in an Instagram feed, where the next trend is just a few clicks away.

H&M's store on Drottninggatan in Stockholm. Photo: Lotte Fernvall

Fast fashion can be described with simple numbers. We buy 60 percent more clothes today than in 2000 and keep each one for half as long.

Around 100 billion new garments are manufactured per year on earth, or 13 for each person. Each is worn an average of seven times. Then it is thrown away.

Bangladesh has in a short time become the world's center for mass production of clothes alongside China.

Fast fashion accounts for almost all exports.

In addition to low wages, the impoverished river country has yet another competitive advantage. Cheap water.

International giants such as Zara, Gap, Walmart and Levi's have been flocking here for a long time. But the biggest buyer of all is Swedish H&M.

When parts of Bangladesh suffered a power outage in early October, the H&M share fell on the Stockholm Stock Exchange. That's how important the country is.

Soma Akhter with Moira the goat. Photo: Lotte Fernvall

The water under Soma Akhter's house shifts to magenta. Mother Nazma, 55, peels onions that she will cook in the earthen oven over an open fire.

Climate change destroyed the land in the home village on the Padma river and forced the family here. She feels rootless, uncomfortable in the slums, but knows that it is not possible to return home.

Moira the goat munches grass from the clay pot.

A neighbor is watching a Bollywood movie at high volume.

The family came here because it is the cheapest to live here.

Only 2000 taka, 200 kroner a month.

We ask who is behind the emissions.

If there is a connection to the H&M factory a couple of hundred meters away.

Soma shakes his head, not daring to point anyone out.

She tugs at the black and white shawl, bites a nail.

The water is turning military green now.

- I dream of children. But they can't grow up here.

A layer of strength is placed on top of the fragile.

Photo: Lotte Fernvall

Photo: Lotte Fernvall

She shows the way out, over the narrow boards, where a diagonal step leads right down into the canal.

The darkness, and the worst smell, is still a few hours away.

To dye clothes, and give them the right softness and texture, a lot of chemicals are used.

Today, the fashion industry is the world's second worst polluter of rivers. Color pigments, salts, heavy metals, ammonia, phenol and other substances are washed into the waterways.

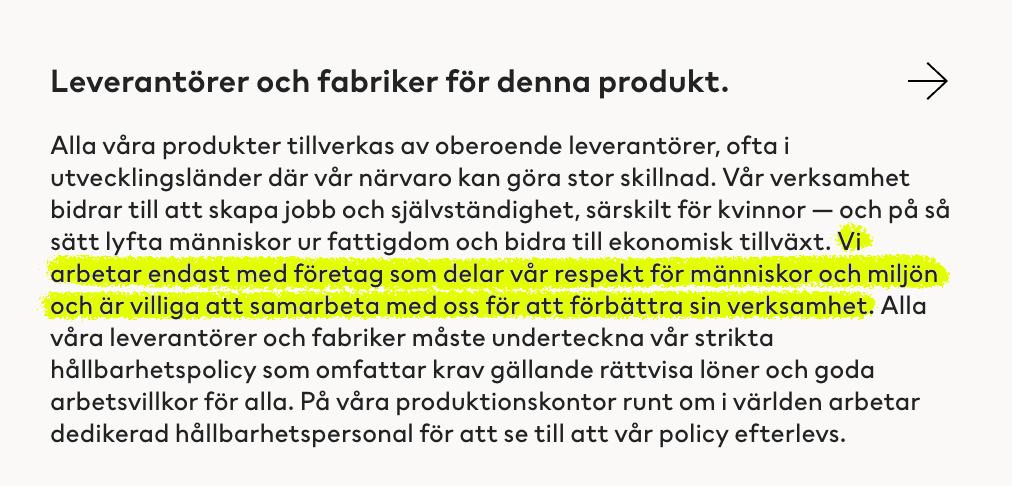

Destroying the water is illegal in Bangladesh. Since 2010, the country's environmental law requires that factories that dye and wash clothes must purify their waste water. Without treatment plant, no license.

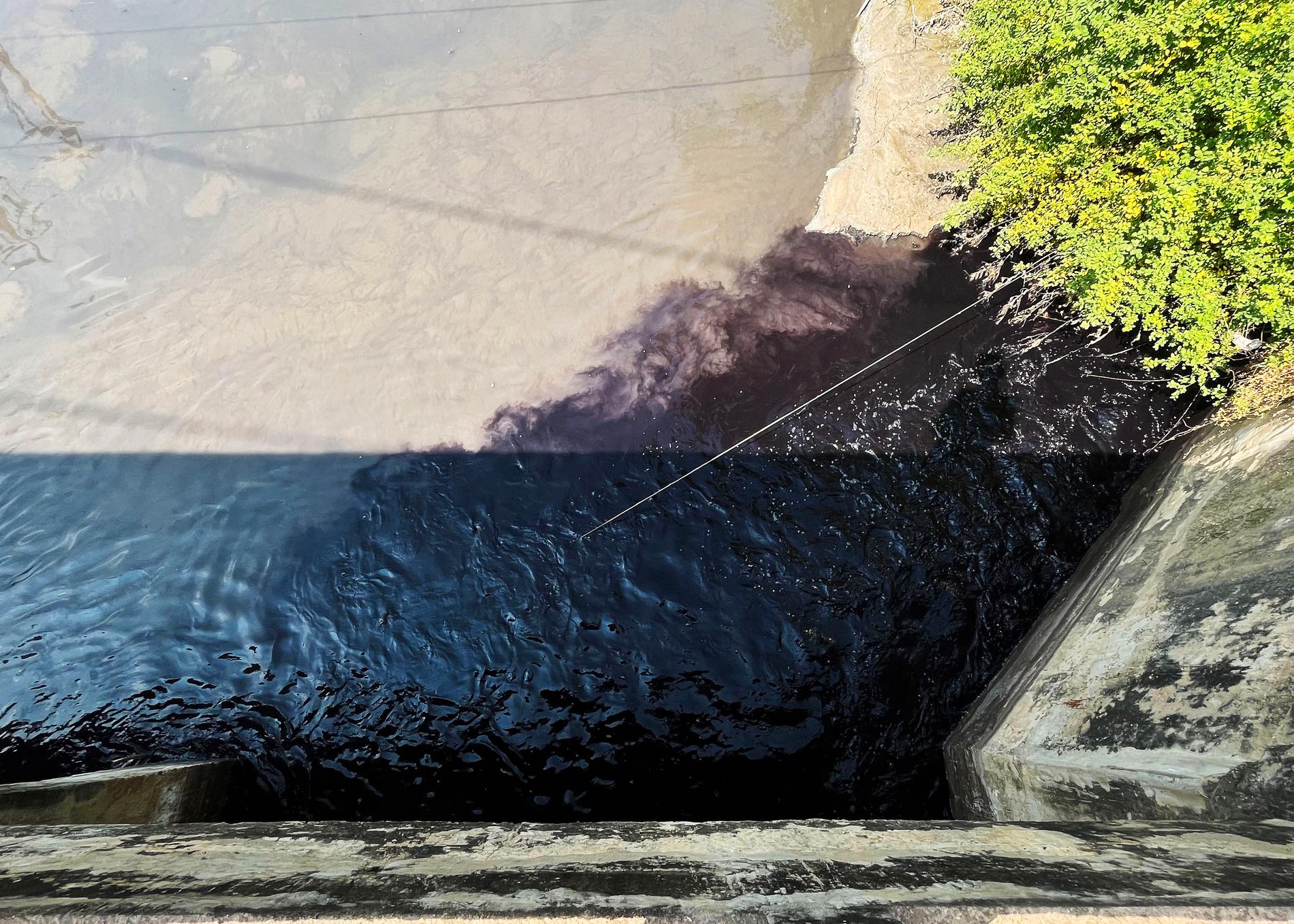

It also violates H&M's requirements. The customers who enter any of the over 4,000 stores worldwide or buy online are assured that each garment is made sustainably, by factories that respect people and the environment.

Yet the water gushes out from under Soma Akhter's house.

Outfall from textile factory in Savar in Dhaka.Photo: Lotte Fernvall

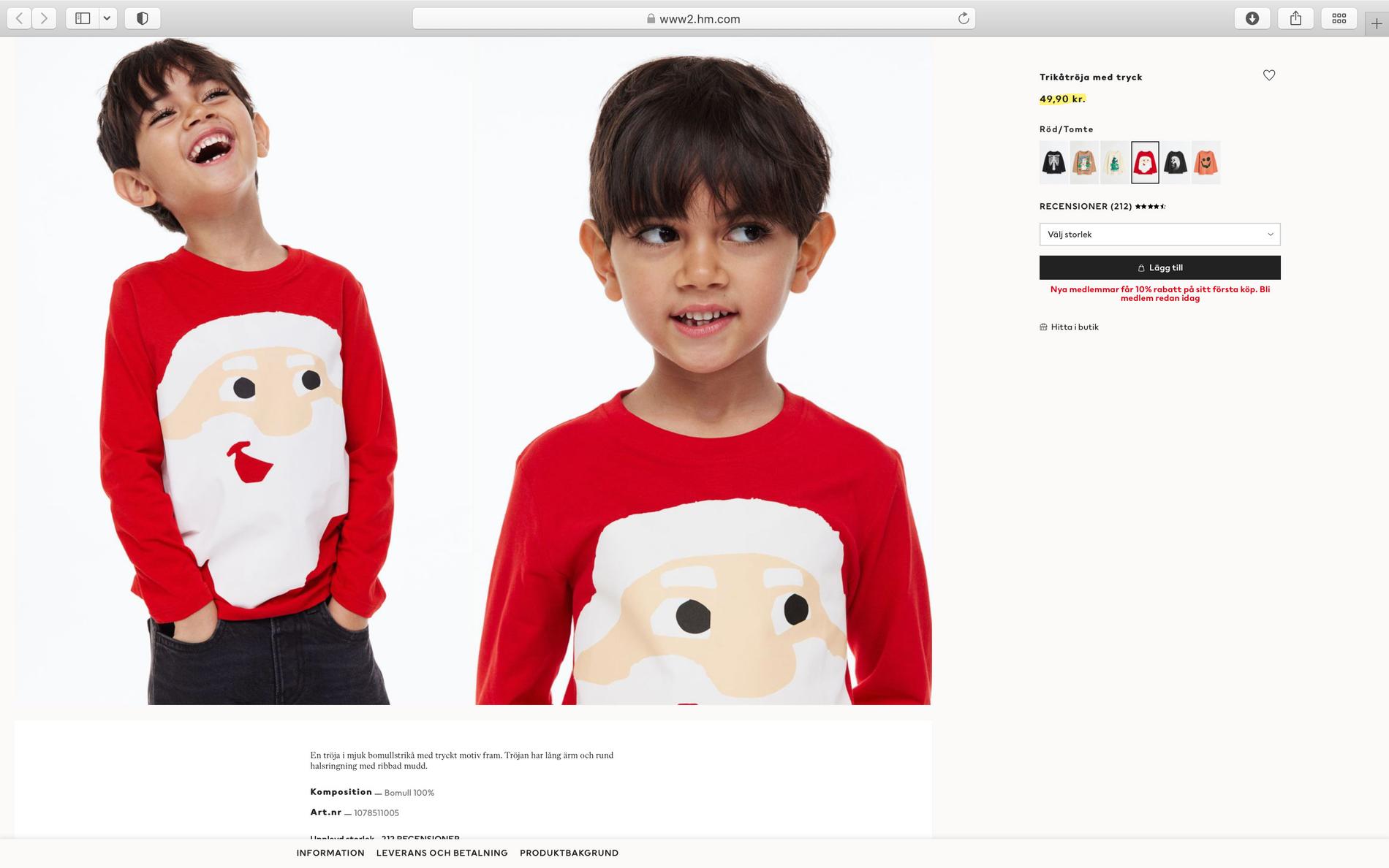

Maybe not everyone knows about it. But with a few determined clicks on H&M's website, you can find both the country of manufacture and the name of the factory where the garment was made.

During one week in September, we click through the roughly 3,000 items listed as new, within the women's, men's and children's range.

In total, we can identify 496 garments manufactured in 96 different factories in Bangladesh. We draw them on a map. Different clusters emerge, an archipelago of factories.

The Santa shirt for SEK 49.90 has been made at Taqwa Fabrics.

1 of 2

One of Bangladesh's most experienced environmental journalists takes part in the map. He has reviewed water pollution for many years and will be our on-site guide.

The plane descends for landing in the dark. Occasional lanterns and fires reveal life down there. Otherwise, the country, with its 166 million inhabitants crammed into a third of Sweden's surface, is invisible.

We don't see any highways. No masts or flashing towers.

A few hours later, the sun will rise and the world's sixth largest city will change shape and be filled with life.

Dhaka was founded in the fertile area between two great rivers four hundred years ago. Now rickshaw pullers with sweaty foreheads and skinny legs jostle with Uber drivers on the overcrowded streets.

You call and honk, try to push forward and find a way through the chaos.

Dhaka, the city of twenty million. Photo: Lotte Fernvall

We are here to review H&M's clothing manufacturing. We randomly select eleven factories, which can be assumed to be representative.

The first stop will be Tongi on the northern edge of the giant city.

The flood waters bring the man to his knees. He lowers the huge net and pulls it up. Again and again, without getting the slightest small fish.

Has no one told him that the ecosystem is collapsing? That the authorities have declared the black mour under us biologically dead?

Not so many years ago, the water was so clear that you could see the bottom, says Paresh Rabidas, a fifty-year-old cobbler with heavy features. It teemed with fish that he used to catch for his family.

- The textile factories have ruined everything, he says, frowning. But what can we do? Go to the Prime Minister and complain?

He mentions a number of factories by name. One of them is on the list of H&M's suppliers - Mascotex.

- Their factory is on the other side of the lake, he says, pointing.

Not so many years ago the river in Tongi was so clear that you could see the bottom. Now the water is jet black. Photo: Lotte Fernvall

Half an hour later we step out onto a chaotic city street. A high wall with barbed wire separates us from the Mascotex factory.

Through the factory windows you can see the fans whipping around and the bare white fluorescent tubes. Floor on floor with seamstresses.

According to H&M's own information, a thousand people work there. Among other things, they sew sweaters and joggers with dinosaur prints for children, which are sold in sets for SEK 279 in Swedish stores.

The guards follow us with their eyes. We play tourists and slip into a market.

Soon we will find people who can point out the factory's drains. It goes under the street, in a closed channel, we learn.

We follow the canal for a couple of hundred meters, seeing nothing but minimal openings.

Finally, it joins the sewage from several other factories. Everything flows out deep below the surface, in the black river.

Who released what cannot be proven.

Outside the Mascotex factory on the northern outskirts of Dhaka.

1 of 2 Photo: Lotte Fernvall

Concrete pillars block the carriageway, we stand still for three quarters of an hour. The solution to the twenty million city's traffic congestion is spelled elevated highways.

Construction has been going on for ten years, but hardly seems to be moving forward. There is talk of the money disappearing into someone's pockets.

A pit stands out like a wound in the urban landscape.

The Rana Plaza textile factory was located here. On April 24, 2013, the building collapsed. At least 1,129 workers died.

The disaster drew attention to disgusting working conditions and life-threatening factories. Some have gotten better since then. But not the water.

We are told that there was never any plan for industrialization.The factories have suspended everywhere.

Nayan Bhuiyan,, second director of the environment department in Gazipur just north of Dhaka, tells our researcher that almost all factories that dye and wash have treatment plants. The problem is that they are not on.

- They don't use the treatment plants unless we visit them, he says.

Sometimes contaminated water is released into the common sewer, sometimes into secret side channels.

On our list we find 36 H&M factories in Gazipur.

We are tracking more factories that sew for the Swedish clothing chain.

Sometimes the places on the map don't match, but we find them some distance away.

Again we discover channels underground. They join the pipes from other factories and run out underwater. The inspector's and residents' designations are not enough. We have to see the emissions ourselves.

It takes almost four hours through morning traffic to reach Sreepur, six miles north of Dhaka.

For centuries, people have built their homes along the rivers, for the cooling winds and the monsoon, which fill the rice fields with water.

Now the link to the story is broken. The fields, which would have secured the children's future, useless.

Photo: Lotte Fernvall

Photo: Lotte Fernvall

Photo: Lotte Fernval

Mariam Masuma, 14, is not really allowed to be here. For as long as she can remember, she has heard the admonitions of the adults.

“Do not go down to the water.”

Last week a cyclone swept past and the rain poured down. The water was diluted and for a few days was a little clearer.

Now she notes that it is just as black again.

Mariam looks out over the beach. With her big black eyes and colorful shawl, she could have been one of the models of the clothing chains.

She says that the swarms of mosquitoes in the wake of the emissions make it impossible to sit outside in the evenings. The slightest drop of water on the skin makes it itch.

- Sometimes the eyes sting and the chest burns.

Her grandfather Nasim waits shirtless outside the traditional mud house where he lived his life, a hundred meters from the beach.

Photo: Lotte Fernvall

- It used to be a mighty river. Boats could go here. We bathed in the water and drank it, says the 70-year-old.

The pollution came with the textile factories about ten years ago.

Nasim remembers how one of his cows went down to drink.

- Then it collapsed and died. On the spot.

Then we understood that it was poisonous.

As recently as last year, he tried to grow rice again.

- It's not possible. Everything just dies.

The clothing factories have wanted to buy the family's land, but according to Nasim only for a fraction of what it should be worth. His son, Mariam's father, has been forced to take a job in one of the factories in order for the family to survive.

The monsoon continues to flood the landscape. And the poison spreads.

No one from the authorities has ever examined the soil or the groundwater.

No one has looked at the health of Mariam and the other children and can say how dangerous it is to live here.

A few skinny goats graze on the grass. Nasim's face shifts, becomes pleading.

- You have seen for yourself what it is like. Please do something for my grandchildren.

There was a time when clothes were worn, patched and mended until they fell apart. Today, 50 billion garments are thrown on Earth within a year of their manufacture.

There are estimates that the fashion industry consumes anywhere between 20 and 200 trillion liter of fresh water. Groundwater is lowered at the same time that huge amounts of microplastics from synthetic fibers are released and end up in fields and in forests and oceans.

Photo: Lotte Fernvall

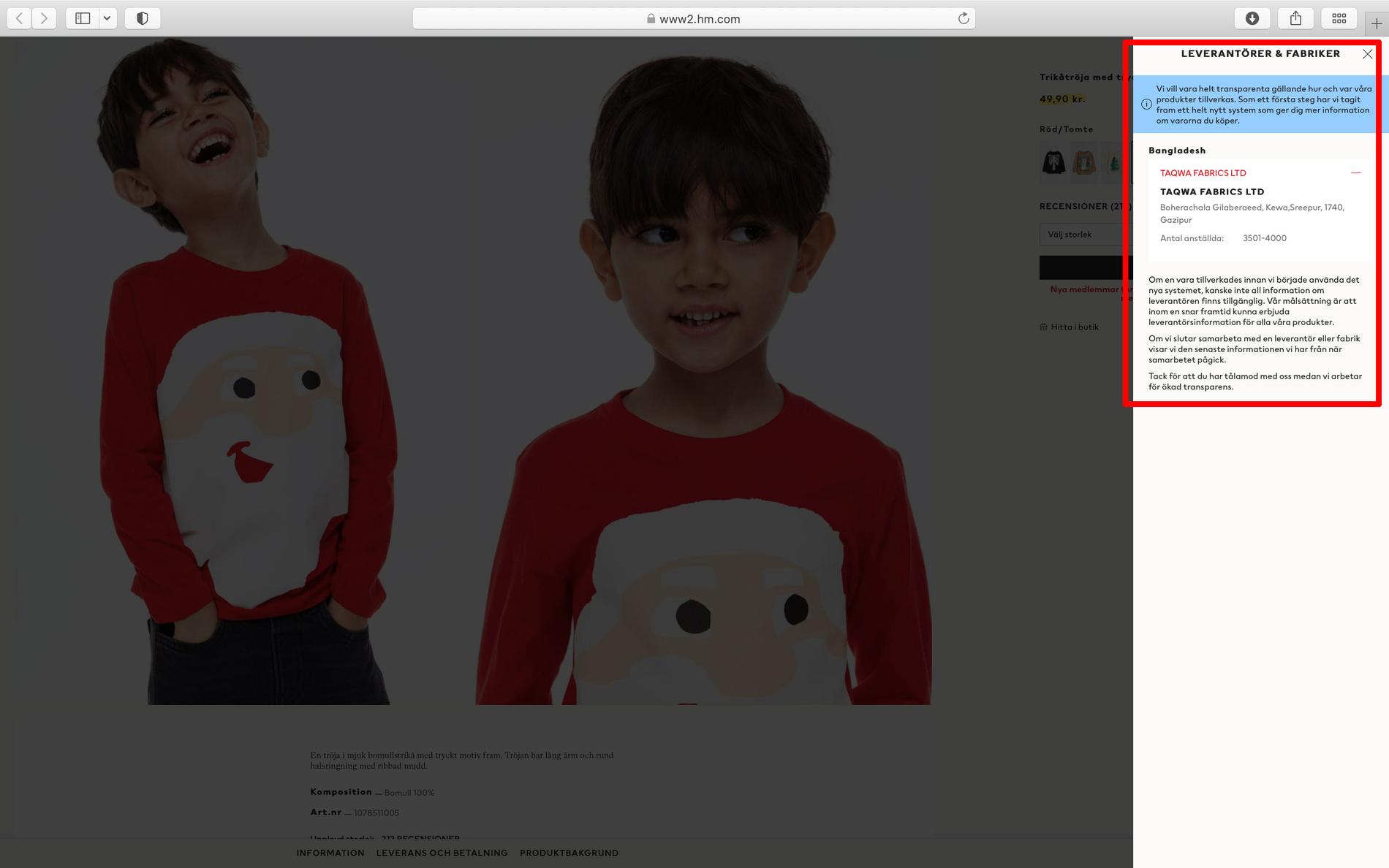

Under a nearby bridge, water is forced out of a concrete pipe.

It is thick and reddish black. Bubbling and wheezing, smelling chemical and rotten at the same time.

The color and stench are clear indicators that the water is contaminated. Soon a cluster of men gathers around us. All live in the area. They are furious.

- One poisons and destroys! Every day they release water in different colors, it's yellow, green and red, says Helal Uddin, 35, a trim man who works as an electrical inspector for the mayor of Sreepur.

He and the other men agree: the contaminated water comes from two nearby factories that share the drain, Taqwa Fabrics and Aswad Composite Mills, both located just a few hundred meters away.

"I saw when they built the pipe and how they later covered it," says Helal Uddin, an electrical inspector in Sreepur. Photo: Lotte Fernvall

Taqwa makes at least six garments that are currently on sale at H&M. Among other things, a small red knitted sweater with Santa print, which is sold in Swedish stores for SEK 49.90.

Aswad Composite Mills is also on H&M's supplier list, although the address goes to the sister factory west of Dhaka. Aswad manufactures, among other things, light blue tops, which are sold for SEK 69.90.

- I have passed here every day since the Taqwa factory was built. I saw when they built the pipe and how two years ago they covered it and built a road on top, says the electricity inspector.

Once he and some other villagers tried to complain. For a few days the water was clear, then everything went back to normal.

- Taqwa's representative said they must pollute. Otherwise the factory will disappear and everyone will lose their jobs.

And the police?

- They don't do anything.

They take bribes.

We look out over a dystopian landscape of screaming birds, plastic bags and garbage.

Helal says respect for nature has been lost; when the water is no longer usable, people dump anything there.

We make our way down to the outlet. The water feels sticky, like tar and ink on the hand.

The garbage is collected next to the damaged waterways. Photo: Lotte Fernvall

The newly constructed village street, which runs on top of the canal, serves as a market. Papaya, ginger, beans, root vegetables and lettuce are sold here - all grown and rinsed in uncontrolled water.

Soon we will be outside the walls of Taqwa Fabrics.

Up to four thousand work behind it, according to H&M's own data.

A beggar who has lost one arm sits by the gate.

In order not to be carried away, we introduce ourselves as hydrologists from a Swedish university, instead of journalists, and ask why the factory releases dirty water.

- We actually run the treatment plant… often, says the guard before he falls silent and summons a manager.

The gates open and close. A truck with chemicals pulls in. Long traders with clothes roll out.

Taqwa Fabrics in Sreepur. Photo: Lotte Fernvall

Two men introducing themselves as engineers come out. They claim, wrongly, that it is normal for the water to be black.

And the stench?

- It... maybe comes from another factory, says one.

Can we see the treatment plant?

- We have to ask the factory manager.

The top factory manager appears. He screws up, pulls away and whispers to the engineers. Then he comes back and parrot-like repeats their message, word for word.

A visit is no longer relevant.

- Email our head office.

All around us, seamstresses pour out for their lunch break. Under the bridge, the water continues to pour out.

According to H&M's own information, around 4,000 seamstresses work at the Taqwa Fabrics textile factory. Photo: Lotte Fernvall

It is repported that the fashion industry is using color like never before, in the wake of the pandemic. In Western cities hundreds of miles from here, gravely shocked pink models walk down catwalks.

"Dopamine dressing" should speed up the neurotransmitters and make us feel good.

According to the World Bank, 72 toxic chemicals are used in dyeing alone. They can lead to various skin diseases and cancer.

On the night.

A dim room, covered in maps dotted with waterways. An office, in downtown Dhaka.

Sharif Jamil, one of Bangladesh's best-known environmental activists and leader of the organization Bapa, explains the background: 30 inspectors throughout Dhaka will check thousands of factories.

- They have neither the knowledge, the equipment nor the capacity. And the penalties are low and the corruption extreme, he says, sipping his cardamom mate.

The clothing industry's tentacles reach deep into politics, we hear. Several ministers and dozens of parliamentarians and mayors own factories themselves.

Some industries pollute openly, others covertly. Sometimes you have two or three factories, one of which is decent, which you show off to the foreign buyers.

- But everyone, or almost everyone, pollutes, says the gray-bearded man.

"The clothing buyers do not take responsibility. The water is being destroyed, while climate change is eating up our land. It's a disaster," says environmentalist Sharif Jamil.

It could be that the treatment plants are broken or have become undersized, when production has increased. But the most common reason is spelled money.

The chemicals required have become more expensive. The electricity price has doubled. Running the treatment plants costs around 5–6 taka (50–60 öre) per litre. For a factory consuming 10,000 liters an hour, twelve hours a day, it can be the difference between profit and loss.

- H&M is like all western buyers. They talk nicely about the environment and working conditions one day only to have forgotten everything the next day, when they negotiate the price. The competition is extreme. It's buyer's market.

The honking from the street penetrates, faintly, as if from another world.

- The clothing buyers do not take responsibility. The water is being destroyed, while climate change is eating up our land. It's a disaster.

The trend cycles are getting shorter, the collections are coming more frequently. The next generation is reached through paid collaborations with influencers on Instagram. The clothes are evicted from the market.

H&M and competitor Zara launched 11,000 new styles between January and April this year. Chinese Shein, who skipped the middle lane, over 300,000. There is talk that fast fashion is transitioning into something else.

They move like a mighty ocean wave through the early morning in Savar, the heart of the fashion district, west of Dhaka.

Young women, by the thousands, who will soon be swallowed up behind the steel gates of the factories.

We are back in Soma Akhter's neighborhood, where fashion colors can be predicted in the color of the sewage.

The school is a stone's throw from her home. The walls are covered in rainbows and photographs of the nation's murdered founders, icons every child is expected to know.

Photo: Lotte Fernvall

Photo: Lotte Fernvall

The smell of fast fashion also reaches here. It makes the children hold their noses at recess and put on their clothes.

Principal Lucky Ahmad is in despair. During the monsoon, the school yard floods and mosquitoes are everywhere.

The principal has requested that the factories stop the emissions or at least erect a barrier against the river, without success. Of the 342 students, at least 90 percent are children of textile workers.

- They can't concentrate. This is ruining their studies.

We enter a classroom, grade five has English.

- Which ones soil? we ask.

- The textile factories, the children answer in chorus.

We talk to a number of residents. Here, too, the testimonies are consistent and specific: the water that runs out next to the school and under Soma Akhter's house comes from al-Muslim, a corporate group that owns several factories.

They point out the canal, which also runs under the road here.

It ends at an eleven-story building that shadows an entire block. A board lists the factories inside, all owned by al-Muslim. The biggest one is on H&M's list.

A.K.M. Knit Wear

The factory, which employs thousands of seamstresses, manufactures 90's Straight Baggy Jeans, price SEK 299. And at least twelve other products. You wash, bleach and dye.

The channel comes from A.K.M Knitwear. The giant factory produces 13 different garments from H&M's collection. Photo: Lotte Fernvall

H&M manufactures around three billion garments every year. The figure should increase further.

The message is clear. The company leads the development towards sustainability in the entire industry. In just a few years, H&M will be 100 percent renewable and circular.

But now the criticism is growing. An audit by the organization Changing Markets Foundation showed that 96 percent of H&M's environmental claims were unfounded or misleading. Something that gave the company a bottom position.

From H&M's website where garments from the factories in Bangladesh we visited are for sale.

The clothing chain's "conscious choice" collection, which customers paid extra for, has in some cases proven to be less durable than the regular range. Both Norwegian and Dutch consumer authorities have cracked down on H&M's environmental promises during the summer and autumn. The Swedish chain has promised improvement.

At the same time, more and more people are asking whether fast fashion can be sustainable at all. Or if what the fashion chains do is just as much about something else.

To create a green facade, to protect sales and growth.

The ferryman Sabur navigates through mazes of water hyacinths, his mouth full of betel root and tobacco. A dead small fish, washed up during the last cyclone, floats forward.

We are in a special export zone, exempt from tax. At the top of the textile pyramid, among the fine factories, far from small laundries, village factories and sprayed cotton fields. This is where the clothes for Adidas were made in the last football World Cup.

Still, it's like getting to the ground zero of environmental destruction. A place so poisoned that the coconut palms along the shores no longer bear nuts.

The polluted water smells rotten and chemical at the same time. Photo: Lotte Fernvall

Shahid Mallick brought us here.

He grew up along the river and has seen it destroyed. Now he divides his time between his position as a climate researcher at the University of Eastern Finland in Kuopio and field studies here.

With his bushy hair and energetic gaze, he looks younger than his 53 years.

Shahid tries to mobilize the people by the rivers against the factories.

- People think they have no chance against the rich and powerful. I want to wake them up.

"You can create hundreds of new factories. But you can't create a new river," says climate scientist Shahid Mallick. Photo: Lotte Fernvall

The sky is pale. The midday heat oppressive, thirty-two degrees. The climate crisis is driving up temperatures, also in the tropics.

Shahid says global warming makes it vital to protect the fresh water we have on Earth. That the lack of water will soon become acute.

- Hundreds of new factories can be created. But you cannot create a new river.

According to the website, H&M has 35 employees who work with sustainability in Bangladesh. None of the many nearby residents we interview have seen any inspectors.

Shahid Mallick urges the foreign chains to involve the residents and get them to report.

- Then you would get a real picture of the emissions. If that's what you want.

The think tank Planet Tracker warned earlier this year that fashion companies are basing their sustainability promises on "zombie data"; information that is false, without credibility or impossible to verify.

Like the water from hidden underground channels.

Factory in Savar, Dhaka. Photo: Lotte Fernvall

Sterling Denim, workplace of more than four thousand textile workers, rises like a colossus over the surrounding shantytown, three miles northwest of Dhaka.

Behind the camera-monitored walls, at least a dozen or so garments are manufactured for H&M. Including skinny fit jeans in children's models, price SEK 249.

The pattern repeats. Once again, the residents show how the sewer pipe was hidden under a nail-straight dirt road. Everything ends on a long pier, in a wetland that slowly fills up with blue-black water.

This will be the eleventh and last H&M factory we visit in Bangladesh. And the fourth that we can link to pollution. Together, the four factories produce at least 39 garments that are now sold at H&M.

Photo: Lotte Fernvall

Photo: Lotte Fernvall

The emissions may constitute a violation of Bangladesh's environmental laws.

- Everyone here knows where the dirt comes from, says Sohaq Islam, 21, a textile worker himself, but at another factory.

He points up to Sterling's building, the only one on this side of the water. Coming up with a story that by now sounds familiar.

- The emissions are worst in the evening, in the dark. Then it is not possible to be here.

Some children fly a homemade kite, the older ones kick a football.

This is a story about people and water. About the clothes we wear and about responsibility.

The light could just as easily have been directed at Kapp-Ahl, which states on its website that the company helps the vulnerable in Bangladesh.

Or Lindex, which claims to "exist" to empower and inspire women from cotton fields to fitting rooms.

Or any of the other Swedish or foreign brands that, unlike H&M, have chosen not to openly report which factories the clothes are made in.

We can also direct the light at ourselves.

It is not poverty that destroys the water in Bangladesh. It is our demand and our abundance.

The Santa shirt from Taqwa Fabrics hangs at the front of H&M's store.

1 of 2

We are back in the H&M store on Drottninggatan in Stockholm. Christmas shopping is underway, employees are folding garment upon garment.

One step down, in front of the entrance to the children's department, it shines like an eye-catcher.

The red children's sweater with Santa print from Taqwa Fabrics. Best price SEK 49.90, the sign shouts.

The text on the inside is smaller and almost hidden, but is there as a reminder of the garment's true price. Made in Bangladesh.

Footnote: During the week, Aftonbladet applied to H&M for an interview. The fashion chain has chosen to respond through a written comment. There, Shariful Hoque, responsible for water issues within the H&M group, states that the company takes the information seriously:

"We are in close contact with our business partners and have started our own investigations to gain further clarity on these specific issues."

Aftonbladet's Staffan Lindberg and Lotte Fernvall on location in Dhaka, Bangladesh.

Aftonbladet's Staffan Lindberg and Lotte Fernvall on location in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Photo:

Inga kommentarer:

Skicka en kommentar