Shooting the Soul of a Nation

Andrew MacGregor Marshall@zenjournalist

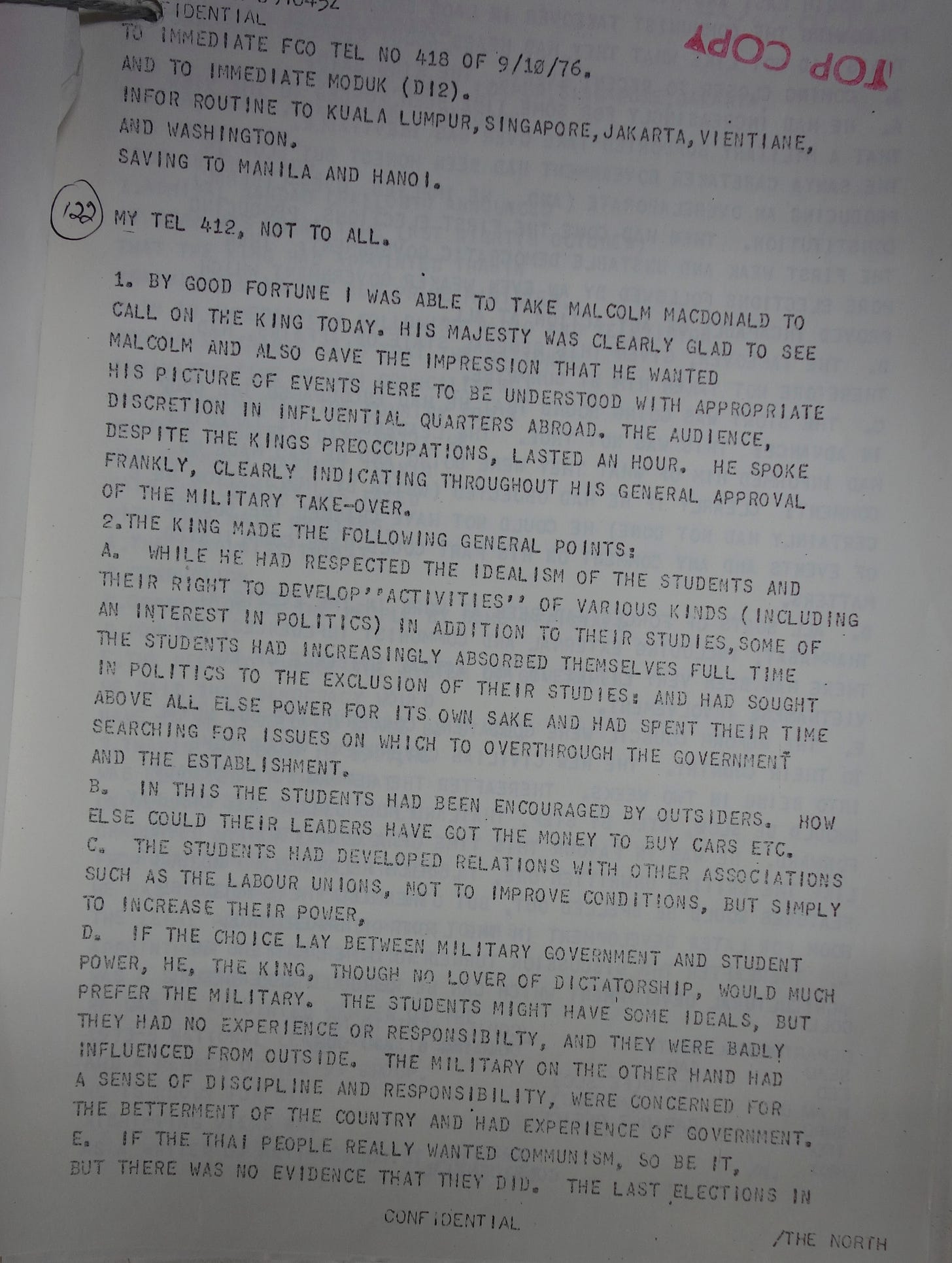

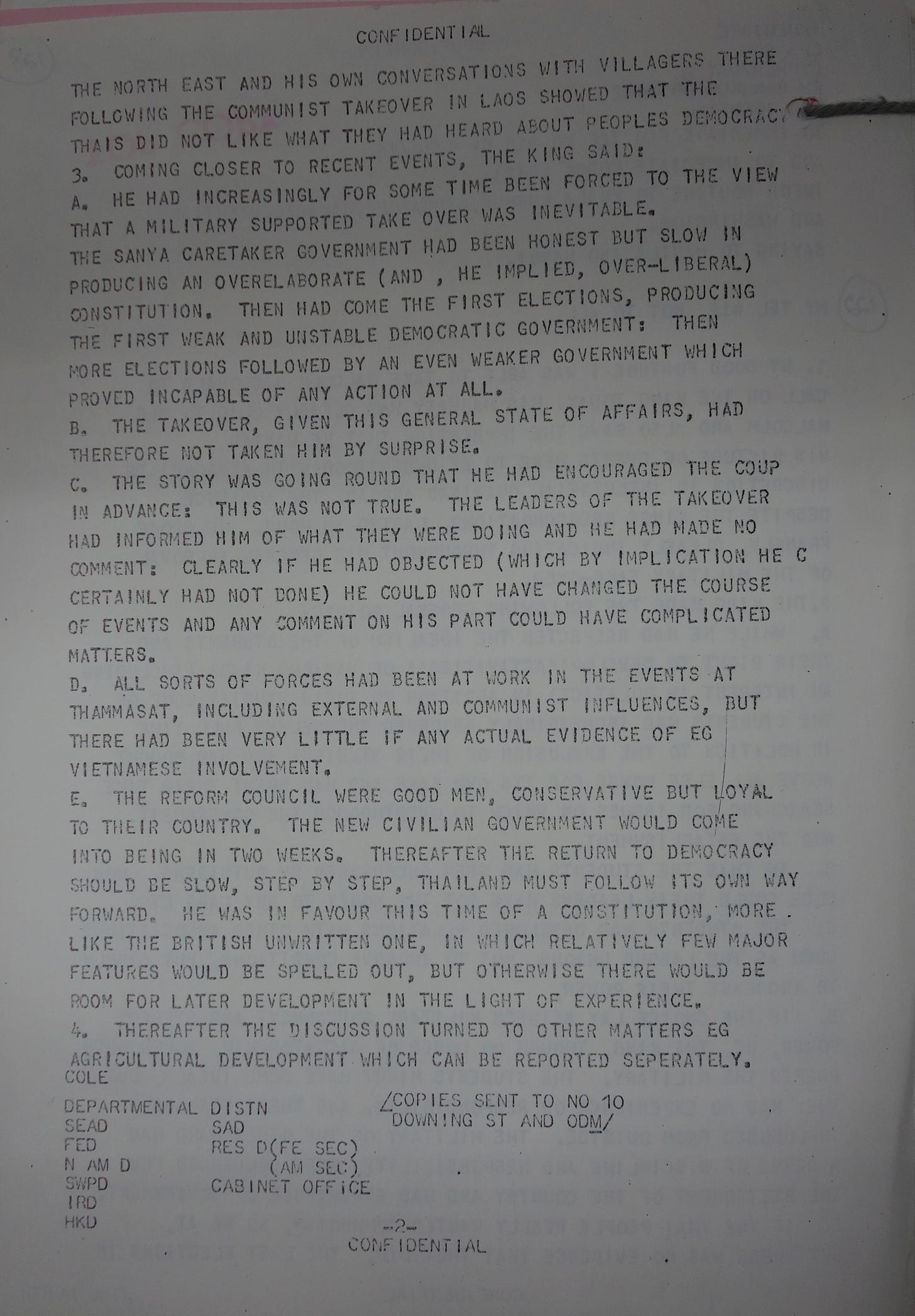

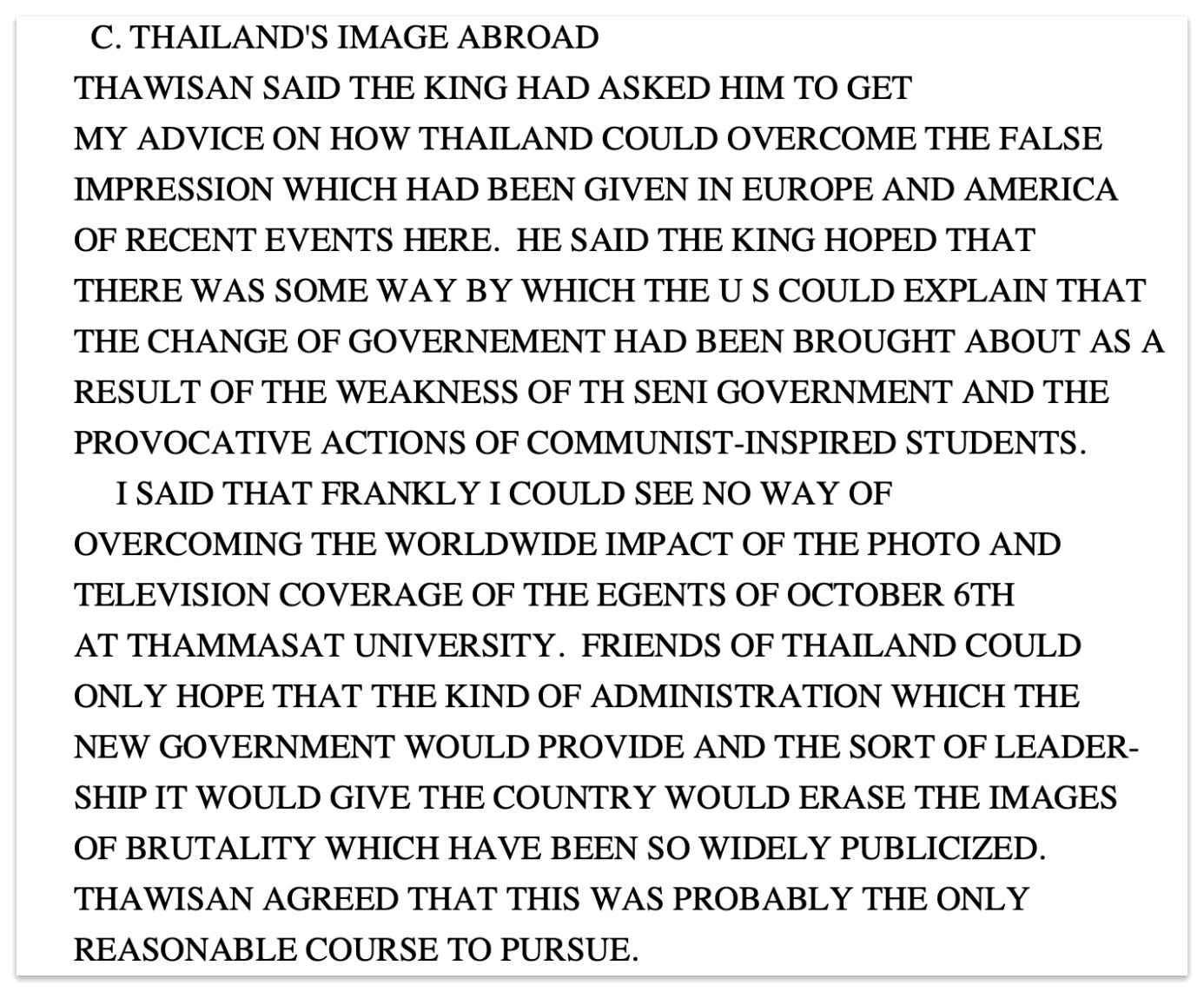

Soul of a Nation, a BBC documentary on the Thai monarchy broadcast in January 1980, is two hours and 42 minutes of ridiculous royalist propaganda. Adding to the absurdity, it is narrated in booming portentous tones by Sir John Gielgud, a towering figure in 20th century British theatre whose mellifluous voice was described by fellow actor Sir Alec Guinness as being “like a silver trumpet muffled in silk”. The script is ludicrously overblown and Orientalist — in the very first sentence of his narration, Gielgud is already declaiming about “the mystic East” — and riddled with outrageous errors throughout. It was produced and directed by a woman obsessed with New Age mysticism and paranormal phenomena who was so passionately royalist that she told Queen Sirikit she loved her. The journalist who worked on the project was appalled by the film and described it to me as “bizarre”. It was in clear breach of BBC standards of impartiality and should never have been broadcast. And yet — in spite of all that — it’s absolutely fascinating. Soul of a Nation is the most remarkable and revealing film ever made about the Thai monarchy. Part of its value is that it lets us see the monarchy’s mythmaking in action, with the royals acting out their roles in a grand theatrical spectacle. It’s beautifully filmed, too. But the best thing about the documentary is that it actually subverts the ham-fisted propaganda it is trying to promote. Although it tries very hard to tell a fake story, huge chunks of reality come crashing through. The BBC team was given unprecedented access to the monarchy — no foreign television crew had ever been allowed to interview Thai royals so candidly and informally. The film gives us an unparalleled insight into the personalities of Bhumibol and Sirikit, showing them to be far from the saintly figures they pretended to be. To understand the contradictions of Soul of a Nation, it’s important to know the story of how it was made. I’ve been fascinated by the film ever since I first saw it, and for several years I’ve been researching this background. The story I uncovered is as extraordinary as the film itself. The tale begins with the appalling massacre of students at Thammasat University on October 6, 1976, by Thai soldiers, police and right-wing vigilantes. The world was shocked by images of the violence, most famously the Pulitzer Prize-winning photograph by Neal Ulevich showing a man using a folding chair to beat the corpse of a student that had been hung from a tree, while a mob laughed and cheered. What was the king fretting about most after these horrific scenes? His reputation. Even more than most monarchs, Bhumibol Adulyadej always cared deeply about his image. The palace propaganda machine — ably assisted by the United States — had spent decades promoting him as a wise, benevolent king working tirelessly for his people. After 1973, when Bhumibol was (misleadingly) credited with kicking out the hated “three tyrants” ruling Thailand and ushering in a new era of democracy, his reputation in Thailand and around the world soared to new heights. He was terrified that the Thammasat massacre had ruined this, and desperate to try to salvage his image. Just three days after the massacre he met an old acquaintance, Malcolm Macdonald, a retired British diplomat who had previously held very senior roles in Southeast Asia and who happened to be visiting Bangkok. A confidential cable recounting their conversation says Bhumibol “wanted his picture of events here to be understood with appropriate discretion in influential quarters abroad”. The king blamed the events at Thammasat on various groups including communists and foreigners. Ten days later, on October 19, US ambassador Charles Whitehouse met Bhumibol’s principal private secretary Thawisan Ladawan over a long lunch. Thawisan, who was the husband of Sirikit’s younger sister Busba, said Bhumibol was extremely worried about the “false impression” created by recent events. Whitehouse recounted their conversation in a secret cable to Washington. Despite Whitehouse’s blunt response to Thawisan, the US and UK were extremely keen to help Bhumibol rehabilitate the reputation of the monarchy. They feared that Thailand was at risk of falling to the communists and believed Bhumibol played a crucial role in holding the kingdom together. In 1978, a new British ambassador arrived in Bangkok to take up his post. The 57-year-old Peter Tripp was a veteran diplomat and obsequious royalist who relished the opportunity to interact with Bhumibol and Sirikit. On August 27 that year, the royal family travelled to a village in Narathiwat province for one of the king’s frequent development trips. As usual, some diplomats and media were brought along. Tripp was there, and so was Bridget Winter, a 46-year-old BBC documentary maker who was researching a television series about various forms of mysticism around the world. Winter was a follower of a New Age movement based on the book A Course in Miracles. According to her own bizarre account of how she got involved with the movement, it all started in February 1975 when she was having coffee one morning at her flat in London with a neighbour, Grace Brooks, who suddenly had a vision of another neighbour being involved in a terrible car crash:

Several days later, Winter said, the accident really happened, exactly as Brooks had foreseen. This led to a conversation with Brooks about telepathy and the paranormal, which led to a discussion about Adolf Hitler (bear with me here) then to a discussion about the “Spear of Destiny”, a fabled artefact reputed to have pierced the side of Christ as he was being crucified and which possessed mystic powers. Via various other twists in the tale, the Spear of Destiny eventually led Winter to attend a talk on A Course in Miracles, which changed her life. Winter said she was captivated observing the royal family during the trip to Narathiwat:

As she was watching, Queen Sirikit came over to talk to her, and the two quickly bonded over their shared interest in paranormal phenomena:

At the dinner, Winter became further enraptured by the royals, Sirikit in particular, and became convinced that the Thai monarchy shared the same principles as A Course in Miracles:

By the time Bridget Winter left her dinner with Bhumibol and Sirikit she was a fanatical devotee of the Thai royals and determined to make a documentary about them, with the full support of the palace. Tripp, the British ambassador, thought this was an excellent plan. They all agreed it was the best way to rehabilitate the image of the Thai monarchy abroad. Winter travelled back to London and pitched the idea to the BBC, telling them that thanks to her personal connections with the king and queen, she could secure unprecedented access for the documentary. The BBC accepted the proposal, but John Gau, the head of current affairs, wanted an experienced journalist on the project. He approached David Lomax, a widely admired 40-year-old correspondent. Lomax died in 2014 but I interviewed him two years earlier about the making of Soul of a Nation. He told me why he was brought on board:

Lomax was legendary for fearlessly asking tough questions — earlier in 1978 he had asked the murderous Ugandan dictator Idi Amin: “Do you eat the hearts of your enemies?” During the interview, Amin had roared with laughter, saying: “Mr Lomax, you are a very brave man.” So Soul of a Nation was riven with contradictions from the start. Winter, who would produce and direct the documentary, was a New Age mystic who revered the Thai royals and wanted to make a hagiography. She was essentially acting as a proxy for the palace, planning to make exactly the kind of propaganda film they wanted. Lomax, who would do the reporting and interviews, was a brilliant journalist who believed in impartiality and asking questions, and wanted to make a factual and balanced documentary about the monarchy. They had totally different visions about what kind of film they were making, and before long, inevitably, tensions erupted. The BBC team made three trips to Thailand during late 1978 and early 1979. Their main facilitators in the palace were Bhumibol’s close confidante and deputy principal private secretary Butrie Viravaidya, and her husband, the half-Scottish “condom king” Mechai Viravaidya. According to Lomax:

While Winter was fixated on temple ceremonies, Lomax was asking questions nobody had ever dared to ask Bhumibol and Sirikit before. He asked Bhumibol about the death of his brother Ananda, and whether he was lonely, and whether the royals were only helping the poor because otherwise they would turn to communism. He asked Sirikit what the communists thought about the monarchy, and whether it was true that the royals were the biggest capitalists in the country. He probably asked plenty even more provocative questions that didn’t make it into the documentary. Several times in Soul of a Nation, Bhumibol and Sirikit are visibly annoyed and uncomfortable during their conversations with Lomax. They were simply not used to being talked to like this. It’s wonderful to watch. Winter was furious, Lomax told me:

Meanwhile, Winter was in regular contact with Tripp at the British embassy, telling him that Lomax was alienating the Thai royal family and putting British interests at risk. Things came to a head over breakfast one morning during the third trip to Thailand. Winter, who was well connected at the BBC, told Lomax he was being removed from the project, and she had phoned director general Ian Trethowan, the most important man in the whole organisation, to get his agreement. The BBC is a large and complex bureaucracy, and the current affairs division fiercely defends its independence from meddling. Lomax’s boss told him to disregard the pressure to leave. But after the team got back to the UK, Lomax was completely frozen out:

Lomax told me Winter took months during 1979 to produce a rough cut of the film:

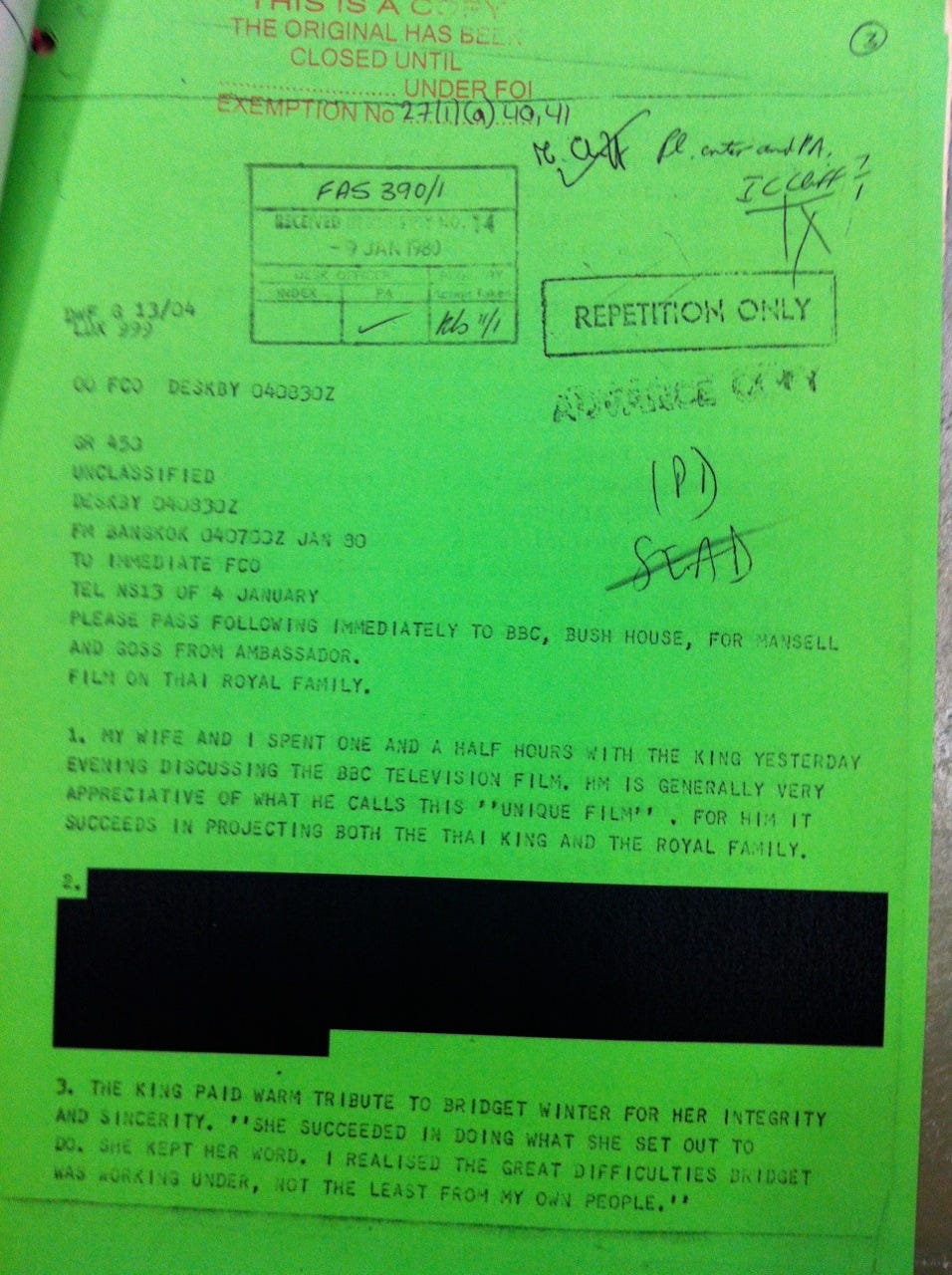

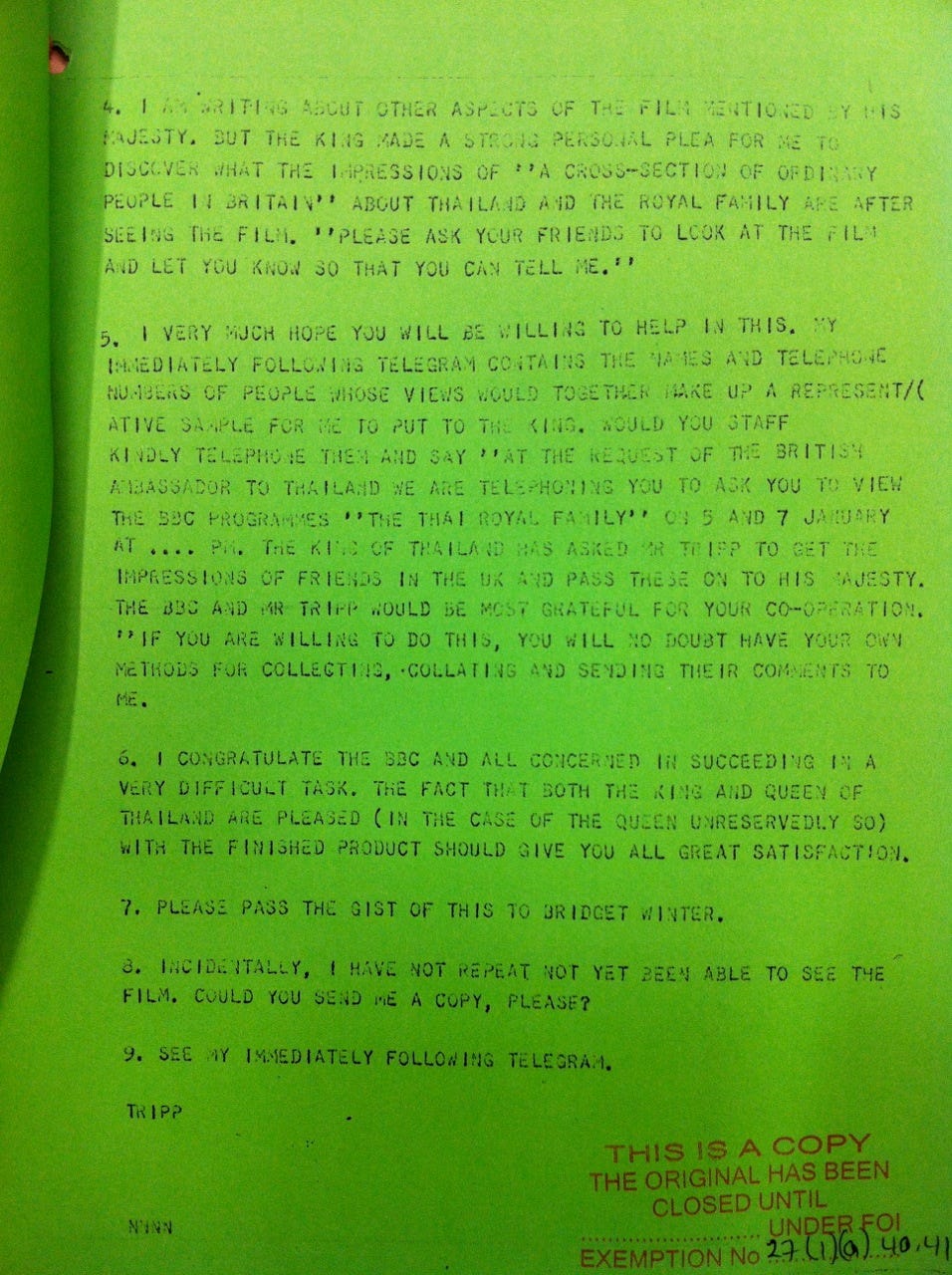

Soul of a Nation had become an embarrassment — and a major headache — for the BBC. They had commissioned an extremely expensive documentary that had turned out to be a preposterous mess. The documentary couldn’t really be fixed, but they couldn’t just scrap it either, after all the cooperation the Thai monarchy had given. They didn’t want to create a diplomatic crisis. Their solution was to split the film into two parts and quietly broadcast it on the much less widely viewed BBC2 channel, in graveyard slots late in the evening, without any fanfare. Part one was scheduled to be broadcast at 9:25 pm on Saturday, January 5, 1980, with part two shown at 10 pm on Monday, January 7. Since each episode was an hour and 20 minutes long, the late timing ensured a tiny audience. The BBC made no effort to promote the film in advance. They felt this was the best way to just make the problem go away with a minimum of fuss. But this was far from the end of the drama. Winter, who had no notion of editorial independence and wanted to be sure that Bhumibol and Sirikit were happy with the film, insisted that it should be shown to them in advance to ensure their approval. This was completely contrary to BBC editorial guidelines, but she enlisted the help of her friend Peter Tripp at the British embassy. The Foreign Office argued that if the royals were unhappy with the film it could damage British relations with Thailand, and after some initial resistance, the BBC bosses caved in. A copy of Soul of a Nation was dispatched to Thailand so the king and queen could have a private viewing of the documentary before it was broadcast. On the evening of January 3, Tripp and his wife spent an hour and a half with Bhumibol and Sirikit to hear their verdict. Tripp conveyed their views in a cable to the BBC the following day, copied to the Foreign Office. It’s an extraordinary document because it demonstrates the extent to which the British authorities had become involved in Soul of a Nation, trampling all over the independence of the BBC. Here’s a copy of the cable in the National Archives in Kew. The reason for the green paper and the poor quality of the printing is that this is not the original document. Although the cable was originally designated unclassified, a decision has later been taken to censor one paragraph because it contains particularly sensitive information, so this is a redacted copy. Tripp wrote that Sirikit was “unreservedly” pleased with the documentary. Bhumibol, however, was less happy. Note the telling use of the word “generally” in paragraph 1:

We can assume that the redacted paragraph 2 goes on to detail what the king was less happy about. The most important thing of all for the king, however, was finding out what people thought of him after seeing the film. He made a “strong personal plea” to Tripp to find out the impressions of “a cross-section of ordinary people in Britain” about the Thai royals: “Please ask your friends to look at the film and let you know so you can tell me.” It was yet another sign of Bhumibol’s obsession with his image and how he was perceived. Tripp was eager to do what he was asked. He told the BBC he would send a list of “the names and numbers of people whose views would together make up a representative sample for me to put to the king”. The BBC was told to phone them up and tell them to watch the documentary “at the request of the British ambassador”. Bhumibol went out of his way to praise Bridget Winter for her “integrity and sincerity”:

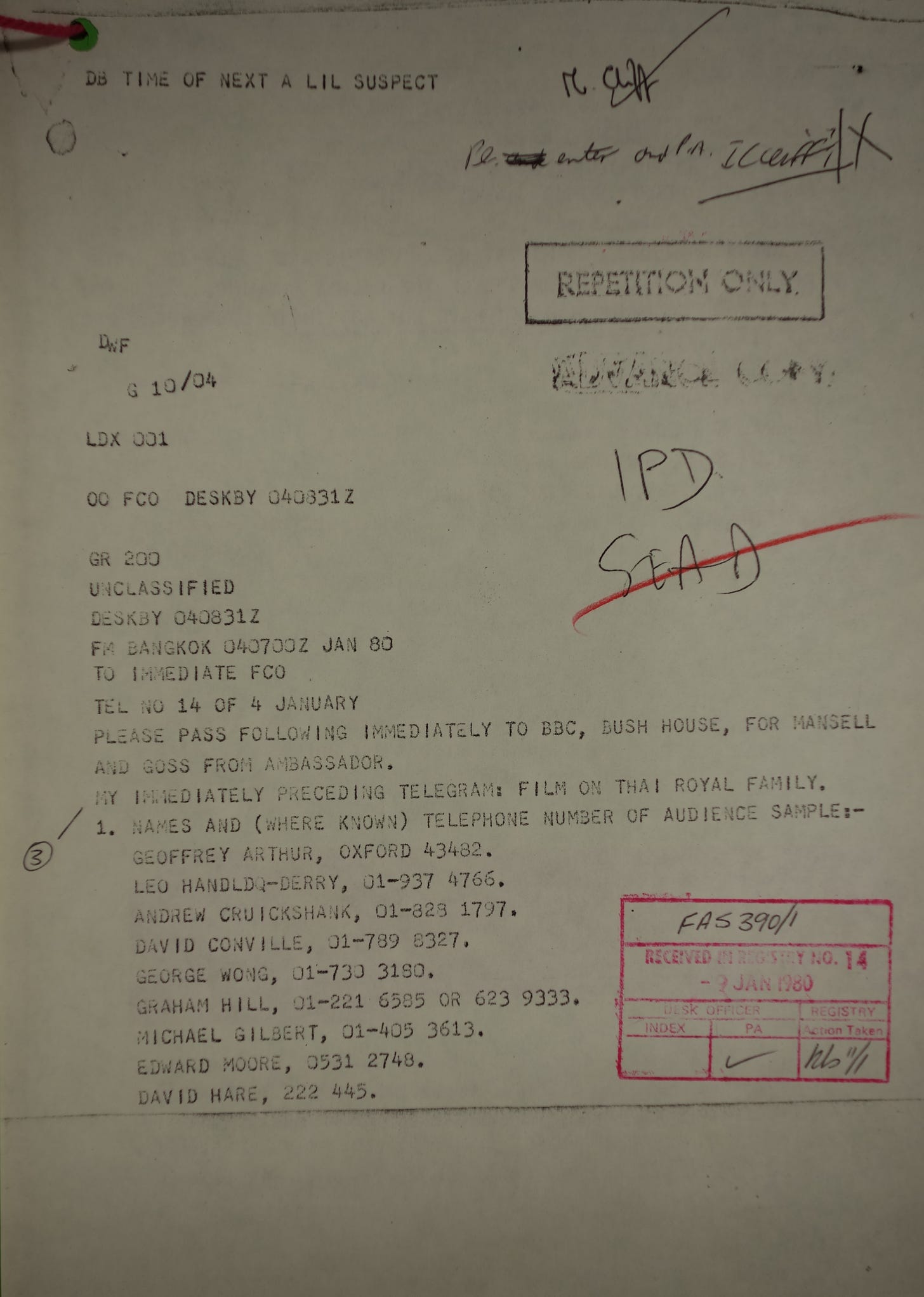

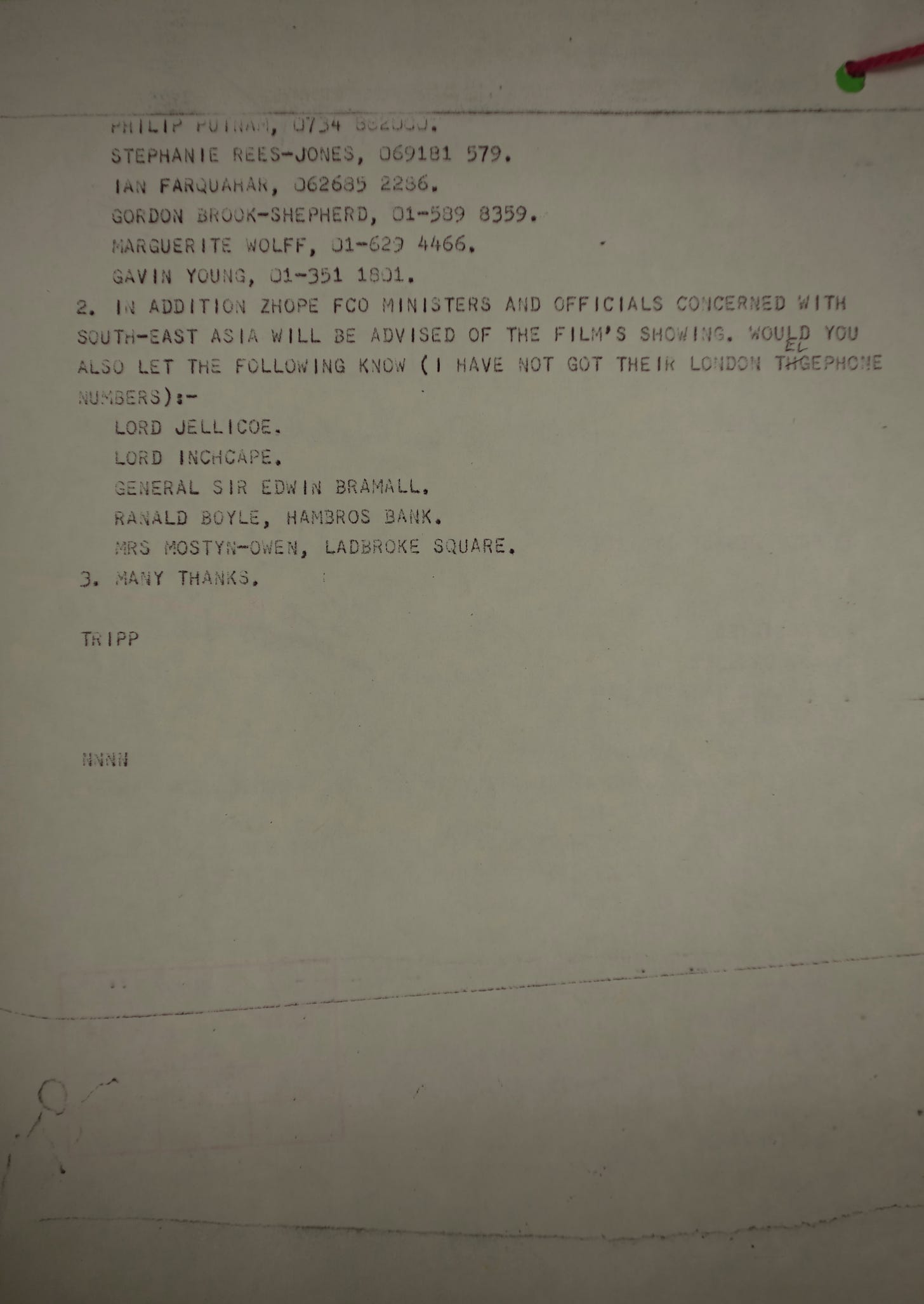

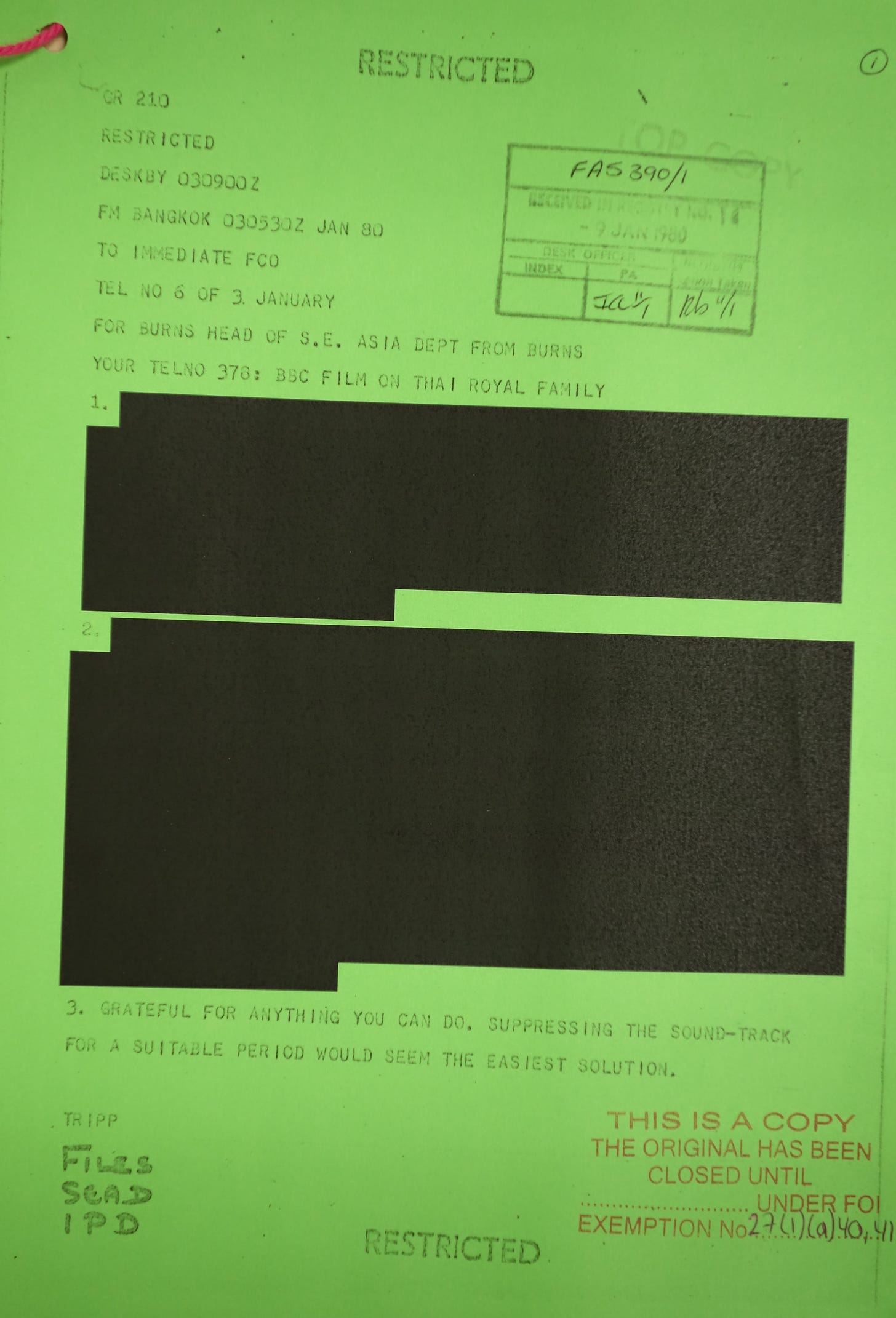

No mention was made of David Lomax, who had caused the royals such annoyance. A short while later another cable arrived at the BBC — the list of 15 friends of Tripp that BBC staff were supposed to phone up to gauge their reaction to the film. They included the playwright David Hare, actor Andrew Cruickshank, theatre director Andrew Conville, pianist Margueritte Wolff, crime fiction author Michael Gilbert, journalist Gavin Young, deputy Sunday Telegraph editor Gordon Brook-Shepherd, and Geoffrey Arthur who was master of Pembroke College, Oxford. Obviously they didn’t represent a cross-section of ordinary people in Britain, but Bhumibol wasn’t really interested in what ordinary people thought anyway — he wanted to know how he was viewed by the British elite. In an even more jaw-dropping intervention, Tripp told the Foreign Office to order the BBC to change the film to fix the issue that Bhumibol had complained about. This was totally irregular — a British ambassador interfering in the content of a BBC documentary on behalf of the king of Thailand. We don’t know exactly what aspect of the film Bhumibol objected to, because the cables have been so heavily redacted. But there is enough information in the documents that the censors missed to piece together some of the facts. It’s clear that the king complained about one specific passage in the script. On January 3, the same evening he had met Bhumibol and Sirikit, Tripp cabled the Foreign Office telling them to intervene with the BBC to get the problem sorted. “Suppressing the sound-track for a suitable period would seem the easiest solution,” he suggested. Even the Foreign Office seem to have been taken aback by this request. A reply from London on January 4 says the BBC had informed them that “it is technically impossible to blank out the explanation of royal vocabulary” — another clue to what Bhumibol was upset about — but that the problem had been smoothed over:

But even though the king had already accepted that no changes could be made to Soul of a Nation, Tripp appears to have been furious. He fired back a cable to London on January 5 — the day part one of the film was due to be broadcast — which has been mostly redacted but includes this demand:

When I first approached David Lomax back in 2012 to talk to him about Soul of a Nation, and told him that the Foreign Office had been trying to interfere with the film right up until it was broadcast, he told me this was nonsense — it simply could never have happened. When I showed him the cables, he was astonished. We won’t know what passage in the film Bhumibol objected to, and whether it really did risk damaging relations with the monarchy or was just a storm in a teacup, until 2046 when the cables are declassified 30 years after his death. It’s highly possible it was a very minor issue. Throughout his life Bhumibol had a habit of pedantry, always finding something to criticise in the work of others, to demonstrate his supposed superiority. If the problem really was an error in an “explanation of royal vocabulary” — presumably the special language rajasap which Thais are supposed to use when discussing the monarchy — it’s hard to see how that could cause an international incident. On the other hand, Tripp clearly thought it was important enough to try to interfere with the editorial independence of the BBC, and presumably Bhumibol had asked him to do so. So maybe the issue was important, at least for Bhumibol. At any rate, the BBC refused to budge, as the Foreign Office told Tripp in a cable a couple of days after the second episode was broadcast. The tone of the cable suggests that even Foreign Office staff were growing weary of Tripp’s histrionics:

It’s actually highly unlikely that the passage could not have been removed, if the BBC had really wanted to do so, which clearly they did not. The cable added that the BBC had informed the Foreign Office that:

In a final slap in the face for the hapless ambassador, the BBC didn’t bother to call his 15 elite acquaintances, saying they were “unable to contact the people listed”. Instead, they would seek public reactions from the BBC audience research panel:

Bhumibol would be getting the views of a cross-section of ordinary people after all. Tripp’s reply is not recorded in the cables. And so, after more than a year of tensions and drama, Soul of a Nation was finally broadcast, late in the evening on January 5 and January 7. The film begins with ravishing footage of a private royal ritual, the naming ceremony for the infant Princess Bajrakitiyabha, with Bhumibol symbolically cutting off a lock of her hair and pouring lustral water over her head as a conch shell is blown. It shows the Brahmin priests who are part of palace rituals alongside chanting Buddhist monks but are very rarely photographed or filmed. Gielgud explains what the names of all the royals mean — Vajiralongkorn is comically translated as “Decorative Lightning” — and then in an increasingly overdramatic voice, he declaims:

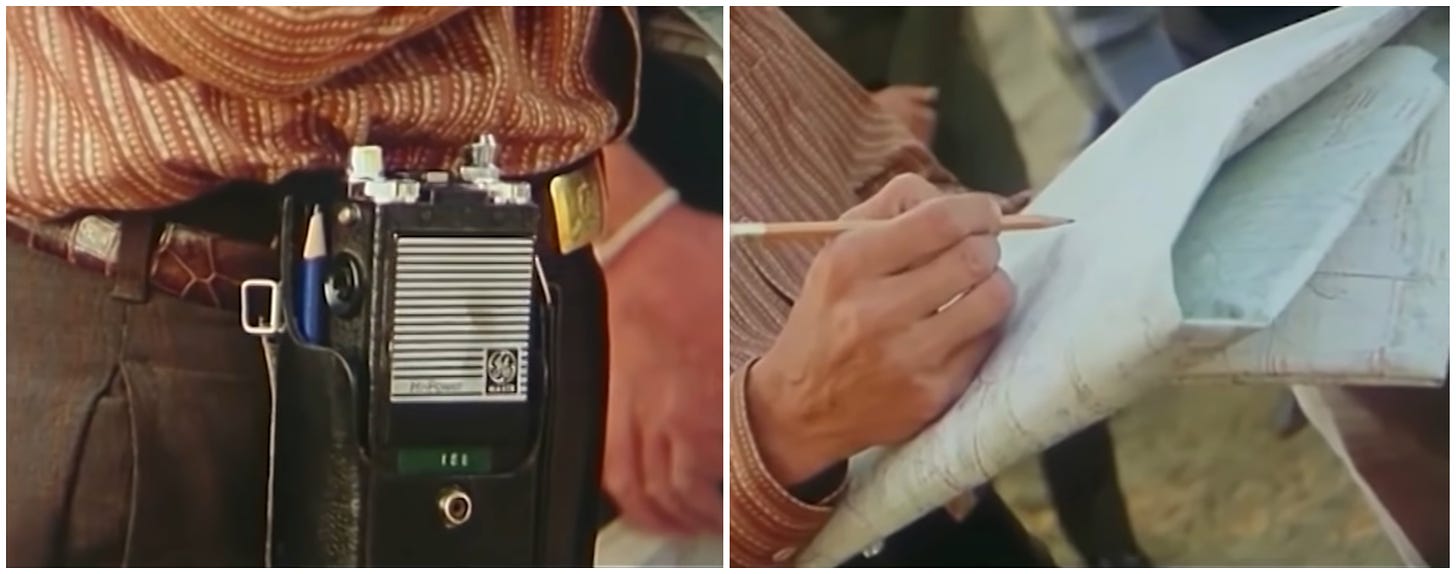

Clearly, this is not the measured tone of a normal, balanced BBC current affairs documentary. We’re five minutes into the film and it’s already clear that Soul of a Nation is batshit crazy. The script, by poet and author Leo Aylen, is full of this kind of melodramatic nonsense. The royals are proclaimed to be the selfless and sacred defenders of Thailand’s ancient culture of “purity, wisdom and peace” which is at risk of being “trampled out of existence by communist slogan-shouters who murder not only anyone who does not agree with them, but also anyone who possesses brains or talent to excite their envy.” Gielgud’s absurdly over-the-top narration, more suited to a Hamlet soliloquy than a serious documentary, makes the whole thing unintentionally hilarious. All the usual myths of Bhumibol’s kingship are wheeled out during the documentary — the visionary but humble monarch spending his days visiting remote villages to solve their problems, armed with a map, walkie talkie, and trusty pencil. In one particularly preposterous sequence that flies so far beyond the BBC’s boundaries of balanced factual reporting that by now we’re on a completely different planet, Gielgud exclaims:

But gradually, as the film progresses, we start to see a truer picture of the monarchy, contrary to the image they are trying to project. This is thanks to the superb journalism of David Lomax, who managed to elicit the reality of the royals. Lomax spoke at length to Bhumibol at Phu Phan Rajanives Palace in the mountains between Sakon Nakhon and Kalasin. The king insisted on being interviewed in his “study” in the palace, an austere room which was packed with dozens of radios chattering away in the background and maps and papers scattered across the floor. Bhumibol sat on the bare wooden floor wearing casual clothes and no shoes, which meant Lomax had to squat awkwardly opposite him. It was a totally unsuitable way to do a TV interview, because of the noise, the mess, and the ridiculous seating arrangements, but it was perfect for how Bhumibol wanted to present himself —a man of action, living simply and frugally, staying up late into the night listening to radio reports from all over his kingdom as he toiled tirelessly to keep the country safe. To hammer home the message, Gielgud intones: “The study in his palace looks and sounds more like a command post.” Sections of the interview are spread throughout the documentary. Bhumibol comes across as a lonely and cantankerous man, spouting meaningless rambling platitudes and homilies that are supposed to sound like deep wisdom. As usual, he is deliberately dour and unsmiling. He has a blankly staring glass right eye and a frequent facial tic. He acts irritated at having to answer questions from Lomax, as if it is distracting him from the crucially important work he has to do. In one riveting sequence, as Bhumibol sits scribbling on maps with a pencil, Lomax asks him what he is actually doing. Bhumibol is unable to give a coherent reply. The king gets even more annoyed when Lomax asks what all the radios are for:

Lomax asks another question that gets to the heart of Bhumibol’s personality:

Again, Bhumibol can only respond with homilies:

Throughout the documentary he says nothing truly insightful or wise. He does, at least, seem to be trying his best, and to sincerely believe that he is doing good. Sirikit makes a considerably worse impression, with an infuriating accent and a simpering laugh. Despite being notorious for extravagance and all-night parties, she makes the outrageous claim that “usually we don’t have much private life, because we are considered father and mother of the nation, so naturally we are all the time with the people”. Her excruciating romanticised account of how she and Bhumibol fell in love is among the highlights of the film. At another point she is filmed tottering around a village in Sakon Nakhon wearing high heels to talk to impoverished locals. In an interview at a military outpost, Sirikit claims soldiers are “loved everywhere” and “have won the heart of the people”. She squirms when Lomax points out that communists “tell villagers that the royal family are the biggest capitalists of all in Thailand”. Sirikit is also filmed flirting with a soldier, praising him as a singer, guitarist and artist. What the documentary makers didn’t know is that the soldier was Narongdej Nanda-Photidej, with whom she was openly infatuated. Bhumibol eventually became so enraged by Sirikit’s affair with Narongdej that he was sent away from Bangkok to the United States as a military attaché, and died in mysterious circumstances in New York in May 1985 after a game of tennis, at the age of just 38. The documentary exposes her as shallow, vain and fake. Discussions with the royal children in Soul of a Nation are much briefer, but they still convey a sense of their personalities. The 26-year-old Vajiralongkorn is mostly absent in the documentary — even back then, the royals knew he was toxic — but in one sequence he is portrayed as a brave soldier risking his life to fight the communist menace. In his brief interview with Lomax his mannerisms are strange, and when he is asked what the pressures of being crown prince are like, his answer is another highlight of the film:

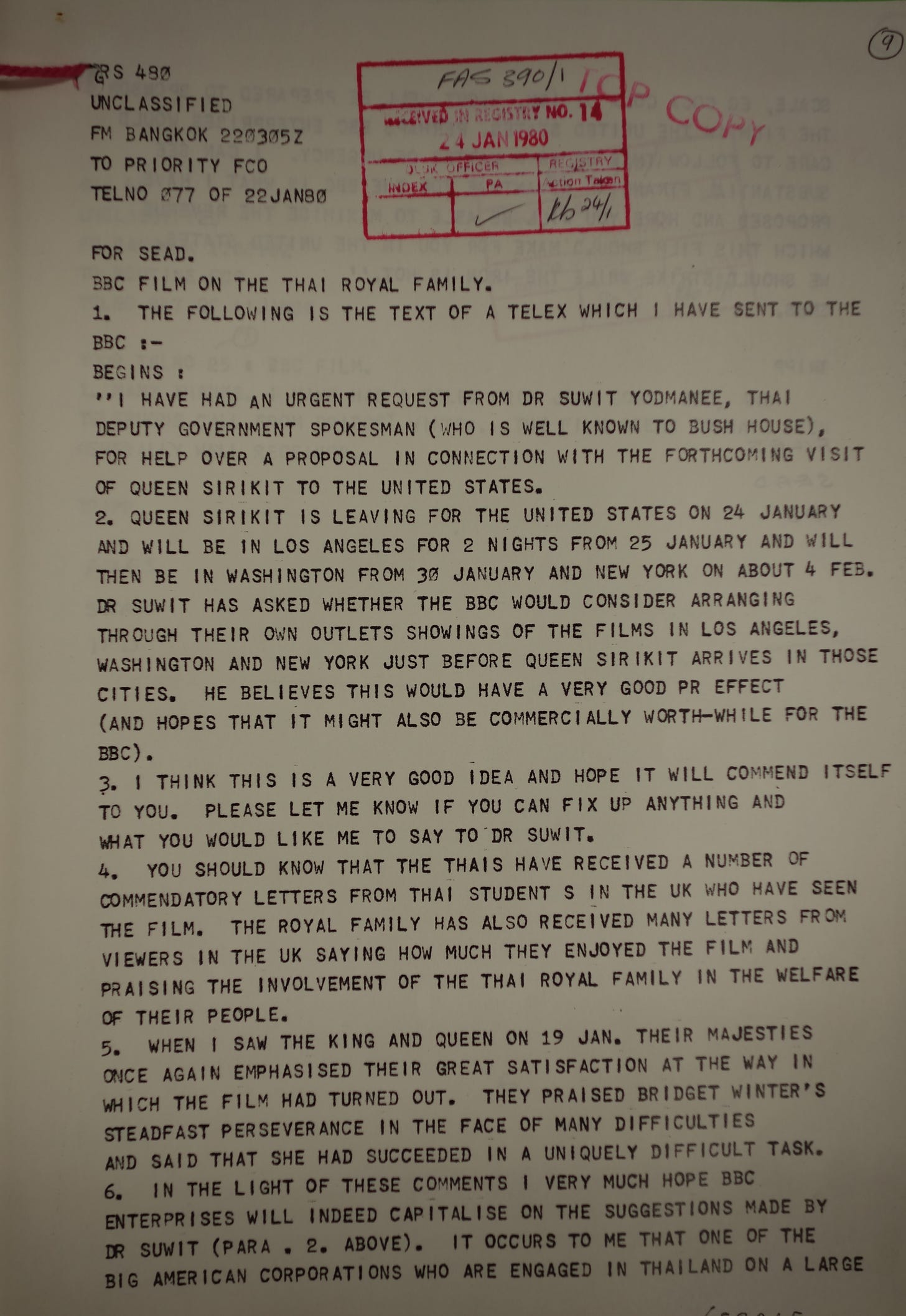

He appears again briefly near the end of the film, talking about his time as a Buddhist monk. The 23-year-old Sirindhorn seems the most likeable of the royals in the documentary — sweet, shy, and trying her best to earnestly answer Lomax’s questions. But the main interview with Sirindhorn is rather marred by the fact that she is discussing Sirikit’s alarming habit of taking children from their parents during her trips around the country if she thought they looked cute, and bringing them back to the palace in Bangkok as pets. As for the 21-year old Chulabhorn, another classic moment in the documentary is when she comes on stage at the Sai Jai Thai Fair to sing When a Child is Born while Geilgud explains — entirely inaccurately — that she is “a successful figure in Thai pop music”. Later, Chulabhorn claims that all the help provided to impoverished villagers is paid for by the royals, not by the government. By the end of Soul of a Nation we feel we’ve been given real insight into the royals as a result of Lomax’s interviews, and that’s what makes the documentary so valuable. We see through the facade — like the moment when the Wizard of Oz is revealed to be just an ordinary man hiding behind a curtain. Sirikit, however, had no understanding that she gave such a bad impression in the film. She thought it made her look wonderful and wasted no time in seeking to use it for self-promotion. At the end of January 1980, she was due to visit the United States with Vajiralongkorn. On behalf of Sirikit, deputy government spokesman Suwit Yodmanee approached Tripp to ask whether the BBC would screen Soul of a Nation in Los Angeles, Washington and New York just ahead of Sirikit’s arrival in each city, which would “have a very good PR effect”. Tripp was enthusiastic about the suggestion, sending a cable to the BBC in which he bizarrely argued that a US firm like Coca Cola or IBM might sponsor the screenings and there could be “substantial financial advantage for the BBC”. “We should strike while the iron is hot,” he told them. There is no evidence the BBC ever considered Tripp’s daft suggestion — after all, they were extremely embarrassed about the film. The US visit turned out to be a PR disaster for Sirikit, as Paul Handley explains in The King Never Smiles:

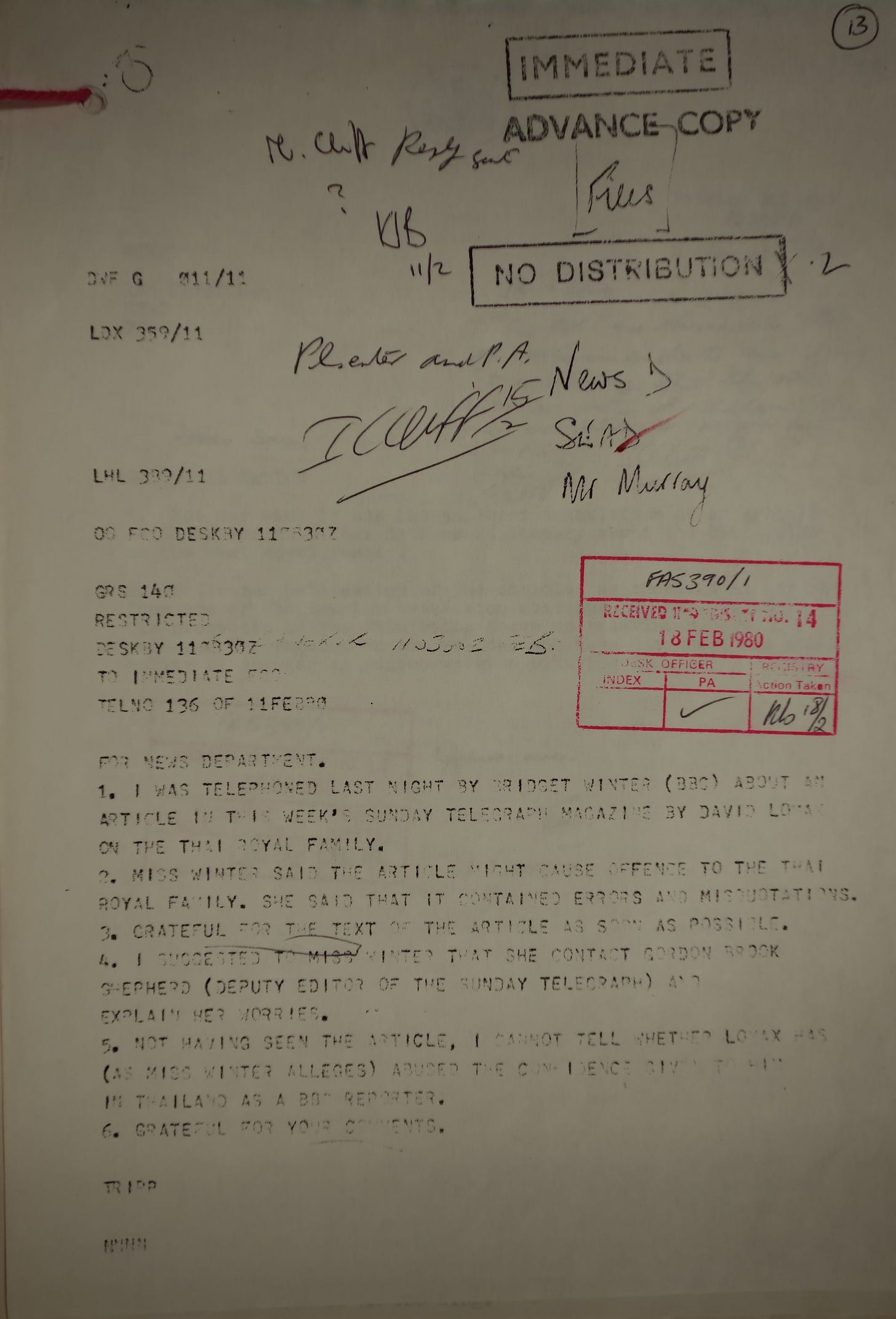

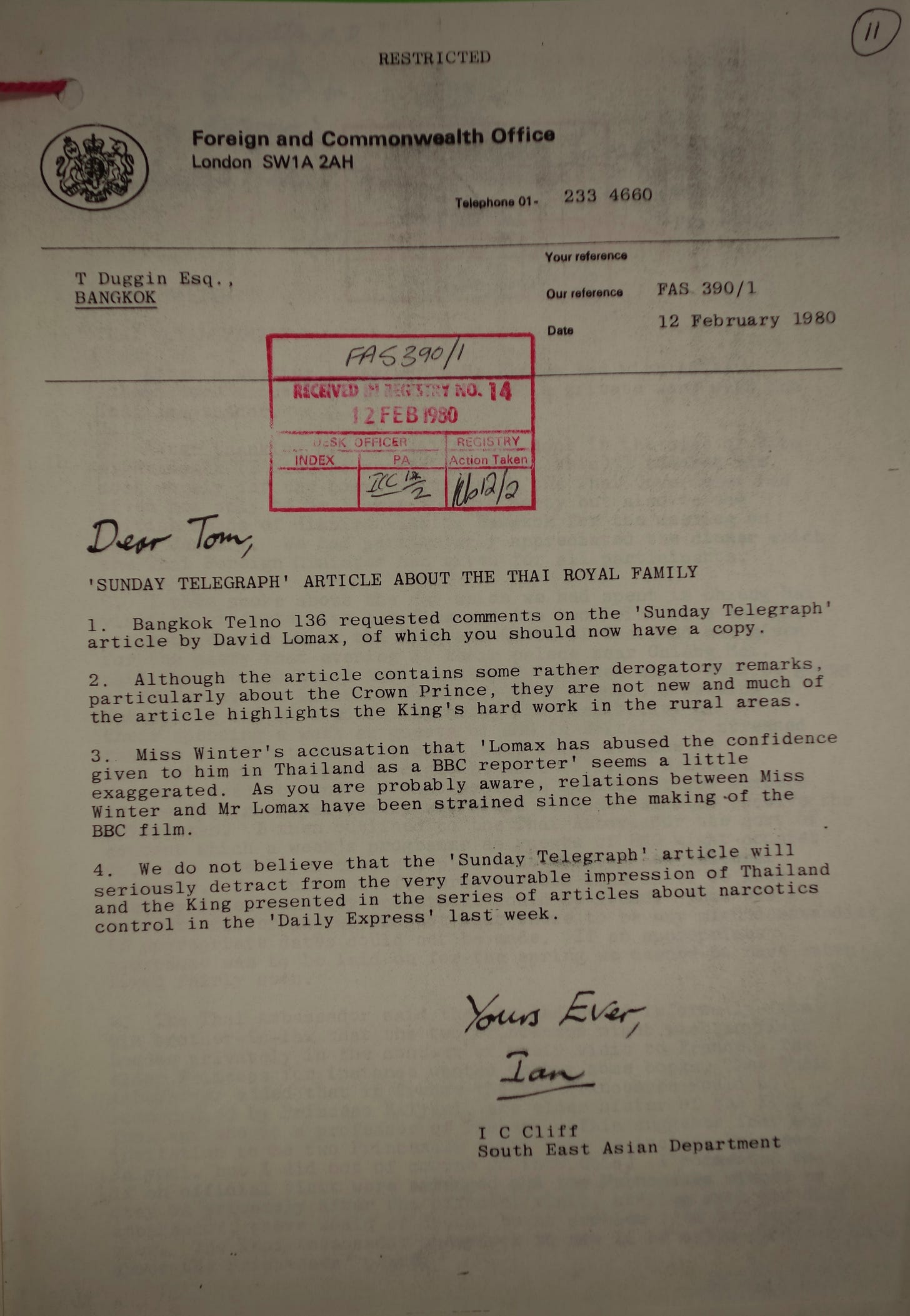

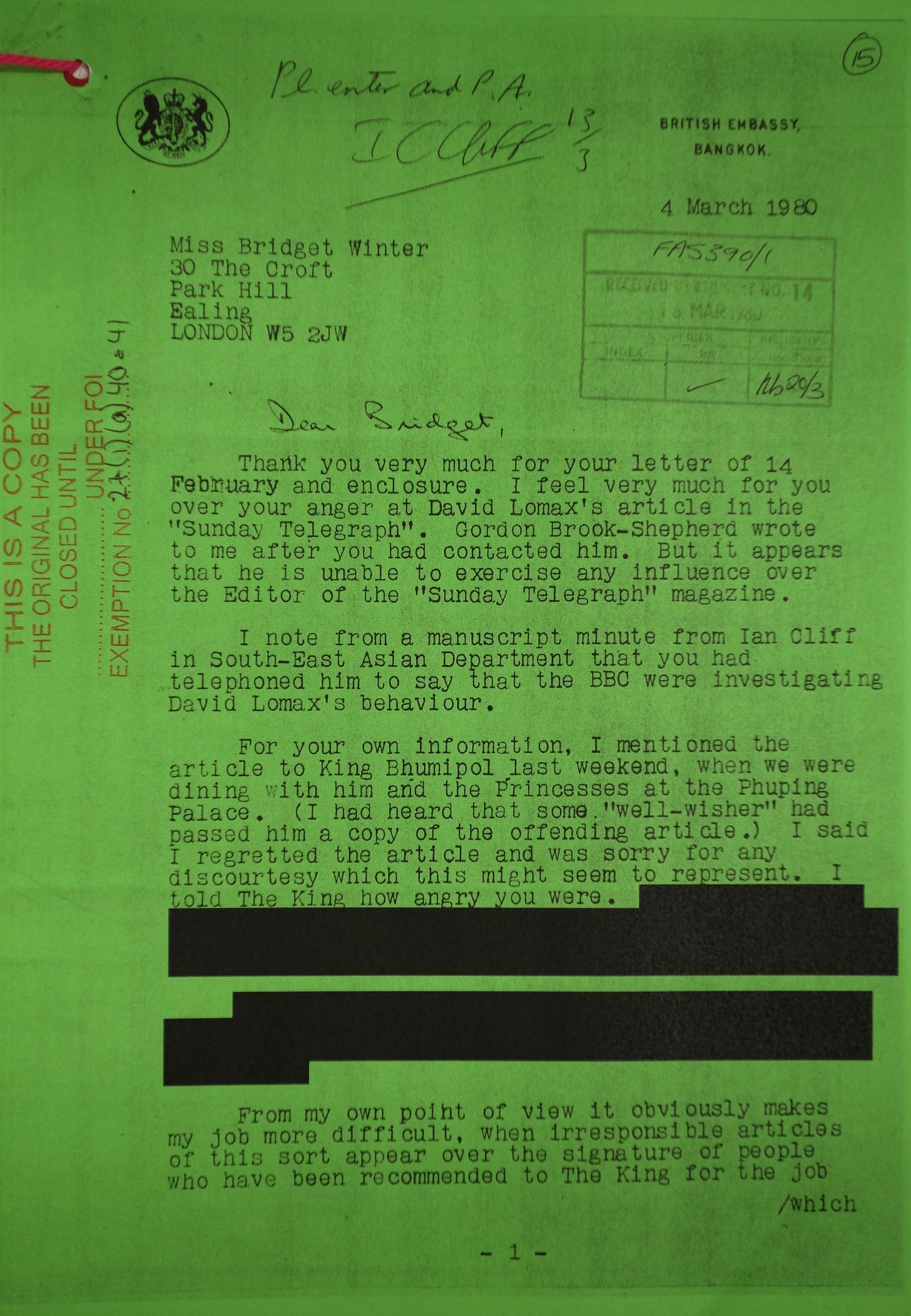

There was one small drama left in the saga of Soul of a Nation. In February, frustrated at how the film had turned out, Lomax wrote an article about Thailand for The Sunday Telegraph Magazine. I’ve been unable to find it, and Lomax didn’t keep a copy, but he told me it “covered many of the points the film had suppressed”. In particular, he wrote about the widespread doubts about the suitability of Vajiralongkorn to be the next king of Thailand. When Winter found out, she was outraged and phoned her friend Peter Tripp in Bangkok, saying the article “might cause offence to the Thai royal family”. He advised her to contact the deputy editor of the Sunday Telegraph to complain. Once again, the Foreign Office in London was relaxed about the issue, cabling Tom Duggin, second secretary at the embassy, to say that “while the article does contain some rather derogatory remarks, particularly about the Crown Prince, they are not new” and that much of the article highlighted the king’s hard work. The cable said Winter’s accusations against Lomax were “a little exaggerated” due to “strained relations” between them. A couple of weeks later, Tripp wrote to Winter, commiserating with her over the incident and telling her that Bhumibol had seen the article — which must have upset her. The interesting sections have been redacted, but it’s clear Tripp still had no understanding of the job that good journalists are supposed to do:

Lomax was reprimanded by his boss John Gau for breaking the terms of his contract by publishing an article without prior permission but faced no further consequences and went on to have an even more stellar career. “All this was a long time ago but I still have vivid memories of the openness and friendliness of the people,” he told me in 2012. “And of the frustration I still feel about what the programme might have been.” |

Inga kommentarer:

Skicka en kommentar