Thanasak’s Trip to Cambodia: Bringing Home the Fugitives?

Wed, 03/09/2014 - 13:44 | by prachatai

Among immediate neighbours of Thailand, Cambodia has become a main concern for the Thai political elite for a number of reasons. From the territorial dispute over the Preah Vihear Temple, or Phra Wihan, to the intimate relationship between Hun Sen and former Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra, these issues have long disturbed those Thai elite, even to the point of them seeing war as an inevitable option.

In the aftermath of the meeting, General Tea Banh told reporters that Cambodia and Thailand agreed to increase the level of economic and trading cooperation. They pledged to enhance security along their common border and tackle transnational crimes. In particular, the Cambodian side sought cooperation from General Thanasak in “looking after” Cambodian workers working in various locations in Thailand. This call was favorably responded by Thanasak who also promised to improve the rights of foreign workers in his country.

However, Cambodia and Thailand have not yet begun the process of dispute settlement over the Preah Vihear Temple. In November last year, as Cambodia returned the verdict of 1962 back to the International Court of Justice (ICJ) for a reinterpretation, the ICJ had confirmed that the Temple belonged to Cambodia and that the two countries’ troops must withdraw themselves from the disputed area of 4.6 square kilometers. General Tea Banh was however confident that the conflict over the Preah Vihear Temple would no longer pose as a throne to the Cambodian-Thai relations.

General Thanasak was accompanied by an army of newly appointed ministers and deputy ministers, including those from the Ministry of Education, Ministry of Transportation and Ministry of Defense—all paid a call to Hun Sen to find ways in boosting bilateral activities.

But why did Thanasak visit Cambodia in such a rush, just a few days after the Thai Cabinet was formed? The Cabinet members have not even been approved by the King. Since the coup of 22 May 2014, Thailand has found itself in desperate need of friends who are willing to endorse the military regime. Most of Thailand’s traditional allies in the West have condemned the illegitimate coup and moved to apply “soft sanctions” against the National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO).

The United States, for example, has suspended financial supports for the Thai army and is now considering to un-invite Thailand for the annual military exercise under the codename Cobra Gold. Meanwhile, the European Union has frozen all ongoing cooperation with Thailand, including the negotiation of the Free Trade Agreement. Together with Australia, the EU has imposed a travel ban on the top leaders of the NCPO. They can no longer travel to Europe and Australia.

At this hour, therefore, supports from neighbouring countries are crucial. China immediately spotted an opportunity to turn Thailand’s political turmoil into its own advantage by moving cozily to the Thai junta in order to offset the American influence in the kingdom. Similarly, Myanmar sent its top military strongman, the Supreme Commander Senior General Min Aung Hlaing, to Bangkok on 4 July 2014. While in Thailand, Aung Hlaing disturbingly said, “The Thai junta is doing the right thing”, presumably in seizing power.

But Cambodia still represents the most sensitive “issue” in Thailand’s foreign relations. Not long after the coup, rumours broke out that Thailand would expel Cambodian illegal workers. Such rumours effectively created an exodus of Cambodian workers back home, causing tensions in bilateral relations, and in particular challenging the regime of Hun Sen whose popularity has relied on popular support. For this reason, Hun Sen may wish to strengthen ties with the Thai junta, in order to ease the workers’ problem, as much as to re-establish his popular mandate in tackling the crisis so swiftly.

More importantly, and from the Thai perspective, Cambodia has in recent years served as a shelter, or a launching pad, of some red-shirt members and now some anti-coup fugitives. Fears become ever more palpable among those who are seeking refuge in Cambodia now that the ties between the two countries at the government level have improved. They fear that Thailand may request Cambodia to deport those fugitives back home. And why would Cambodia not go along with such request?

Thailand signed a Treaty of Extradition with Cambodia and the two countries have since been obliged to extradite criminals to serve their sentences. However, even at the presence of such treaty, it has become an international norm in which no country in the world would extradite any prisoners convicted in political crimes. In other words, in normal circumstances, Thai fugitives in Cambodia must be protected by the Cambodian government, either by offering them a refugee status or dispatching them to the third countries.

But politics, here, there or anywhere, is like a ship sailing in an unpredictable sea. It remains unpredictable whether the Hun Sen government will continue to allow the anti-coup fugitives to reside in the country. On the one hand, Hun Sen may take this opportunity to befriend Thailand and reconstruct an environment of security along the border. On the other hand, he may calculate that the Thai fugitives are too useful to be kicked out, as some sorts of a bargaining chip vis-à-vis the Thai military regime.

Pavin Chachavalpongpun is Associate Professor at Kyoto University’s Centre for Southeast Asian Studies.

Pavin Chachavalpongpun is Associate Professor at Kyoto University’s Centre for Southeast Asian Studies.

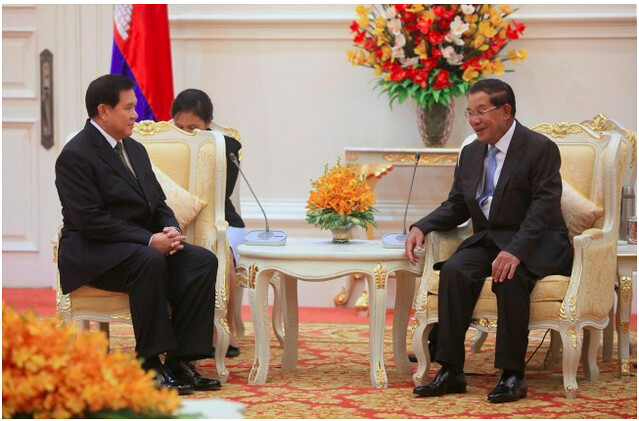

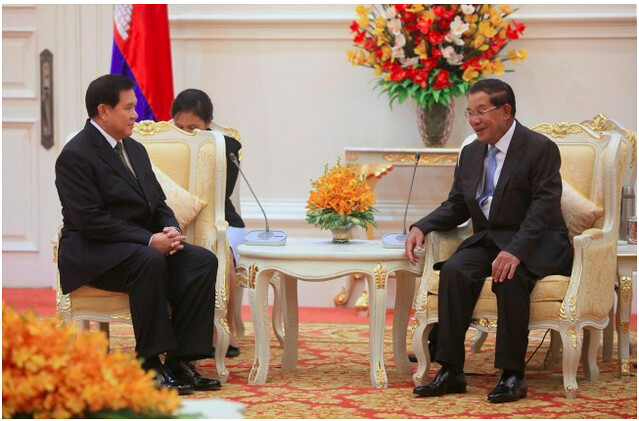

General Thanasak Patimaprakorn, Deputy Prime Minister and Foreign Minister, met with Prime Minister Hun Sen of Cambodia, 1 September 2104.

As soon as General Thanasak Patimaprakorn, Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces, has been appointed Deputy Prime Minister and Foreign Minister, he embarked on an official trip to Cambodia to consolidate bilateral ties with the Cambodian leadership, on 1 September 2014. In Phnom Penh, General Thanasak had a chance to meet with Prime Minister Hun Sen and General Tea Banh, Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Defense. The mood for a celebration could not have been more joyous.Among immediate neighbours of Thailand, Cambodia has become a main concern for the Thai political elite for a number of reasons. From the territorial dispute over the Preah Vihear Temple, or Phra Wihan, to the intimate relationship between Hun Sen and former Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra, these issues have long disturbed those Thai elite, even to the point of them seeing war as an inevitable option.

In the aftermath of the meeting, General Tea Banh told reporters that Cambodia and Thailand agreed to increase the level of economic and trading cooperation. They pledged to enhance security along their common border and tackle transnational crimes. In particular, the Cambodian side sought cooperation from General Thanasak in “looking after” Cambodian workers working in various locations in Thailand. This call was favorably responded by Thanasak who also promised to improve the rights of foreign workers in his country.

However, Cambodia and Thailand have not yet begun the process of dispute settlement over the Preah Vihear Temple. In November last year, as Cambodia returned the verdict of 1962 back to the International Court of Justice (ICJ) for a reinterpretation, the ICJ had confirmed that the Temple belonged to Cambodia and that the two countries’ troops must withdraw themselves from the disputed area of 4.6 square kilometers. General Tea Banh was however confident that the conflict over the Preah Vihear Temple would no longer pose as a throne to the Cambodian-Thai relations.

General Thanasak was accompanied by an army of newly appointed ministers and deputy ministers, including those from the Ministry of Education, Ministry of Transportation and Ministry of Defense—all paid a call to Hun Sen to find ways in boosting bilateral activities.

But why did Thanasak visit Cambodia in such a rush, just a few days after the Thai Cabinet was formed? The Cabinet members have not even been approved by the King. Since the coup of 22 May 2014, Thailand has found itself in desperate need of friends who are willing to endorse the military regime. Most of Thailand’s traditional allies in the West have condemned the illegitimate coup and moved to apply “soft sanctions” against the National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO).

The United States, for example, has suspended financial supports for the Thai army and is now considering to un-invite Thailand for the annual military exercise under the codename Cobra Gold. Meanwhile, the European Union has frozen all ongoing cooperation with Thailand, including the negotiation of the Free Trade Agreement. Together with Australia, the EU has imposed a travel ban on the top leaders of the NCPO. They can no longer travel to Europe and Australia.

At this hour, therefore, supports from neighbouring countries are crucial. China immediately spotted an opportunity to turn Thailand’s political turmoil into its own advantage by moving cozily to the Thai junta in order to offset the American influence in the kingdom. Similarly, Myanmar sent its top military strongman, the Supreme Commander Senior General Min Aung Hlaing, to Bangkok on 4 July 2014. While in Thailand, Aung Hlaing disturbingly said, “The Thai junta is doing the right thing”, presumably in seizing power.

But Cambodia still represents the most sensitive “issue” in Thailand’s foreign relations. Not long after the coup, rumours broke out that Thailand would expel Cambodian illegal workers. Such rumours effectively created an exodus of Cambodian workers back home, causing tensions in bilateral relations, and in particular challenging the regime of Hun Sen whose popularity has relied on popular support. For this reason, Hun Sen may wish to strengthen ties with the Thai junta, in order to ease the workers’ problem, as much as to re-establish his popular mandate in tackling the crisis so swiftly.

More importantly, and from the Thai perspective, Cambodia has in recent years served as a shelter, or a launching pad, of some red-shirt members and now some anti-coup fugitives. Fears become ever more palpable among those who are seeking refuge in Cambodia now that the ties between the two countries at the government level have improved. They fear that Thailand may request Cambodia to deport those fugitives back home. And why would Cambodia not go along with such request?

Thailand signed a Treaty of Extradition with Cambodia and the two countries have since been obliged to extradite criminals to serve their sentences. However, even at the presence of such treaty, it has become an international norm in which no country in the world would extradite any prisoners convicted in political crimes. In other words, in normal circumstances, Thai fugitives in Cambodia must be protected by the Cambodian government, either by offering them a refugee status or dispatching them to the third countries.

But politics, here, there or anywhere, is like a ship sailing in an unpredictable sea. It remains unpredictable whether the Hun Sen government will continue to allow the anti-coup fugitives to reside in the country. On the one hand, Hun Sen may take this opportunity to befriend Thailand and reconstruct an environment of security along the border. On the other hand, he may calculate that the Thai fugitives are too useful to be kicked out, as some sorts of a bargaining chip vis-à-vis the Thai military regime.

Pavin Chachavalpongpun is Associate Professor at Kyoto University’s Centre for Southeast Asian Studies.

Pavin Chachavalpongpun is Associate Professor at Kyoto University’s Centre for Southeast Asian Studies.

Inga kommentarer:

Skicka en kommentar