The palace and the pandemic

Thailand's royals are relentlessly trying to exploit the coronavirus crisis for propaganda, with disastrous consequences for the kingdom

I. Never let a good crisis go to waste

Thailand is on the brink of catastrophe as the Delta variant of the coronavirus rampages through the country. People are dying in the streets, with their bodies lying unclaimed for hours. Crematoriums are struggling to cope, and one literally collapsed under the strain of burning so many corpses. Hundreds of thousands of businesses that have barely managed to survive this long will fail in the weeks and months ahead as ever stricter lockdowns are imposed. More than 1.5 million people have fallen into poverty, raising the total above five million. There is no hope of the kingdom fully reopening in October, as prime minister Prayut Chan-ocha promised last month. There is pervasive fear about what the next few months will bring.

But for the royal family, it’s a perfect opportunity for more shameless self-promotion and patronising propaganda.

An image posted on Facebook by Chulabhorn Hospital earlier this month (and later deleted) shows people waiting in a crowded room to be inoculated with the Chinese vaccine Sinopharm. Propped up in their laps are signs with the slogan “วัคซีนพระราชทาน” — “royally bestowed vaccine” — written in the special rajasap language used when mentioning matters related to the monarchy.

Their embarrassment and shame at having to be humiliated like this just to get vaccinated is clear from the image.

Princess Chulabhorn, the youngest sibling of King Vajiralongkorn, gave herself the power to import vaccines independently of the government on May 26. An edict published late in the evening in the Royal Gazette, and signed by the 64-year-old princess, decreed that the Chulabhorn Royal Academy, her research and education institute, had been granted the the authority to procure coronavirus vaccines, medicines and medical equipment.

It was a clear demonstration of where real power lies in Thailand. At the stroke of a pen, the palace can override government policy and do whatever it wants. Chulabhorn didn’t even bother to consult the cabinet in advance — public health minister Anutin Charnvirakul was blindsided and admitted he had been unaware of the plan until it was announced.

Anger was mounting at the government’s shambolic vaccine procurement strategy, as the kingdom fell ever further behind its neighbours in inoculating the population, and a wave of infections that began in high-end Bangkok hostess bars spread through the kingdom. Chulabhorn’s intervention was widely interpreted as a rebuke of the government’s failings.

Chulalongkorn University professor Thitinan Pongsudhirak observed that “this vaccine bombshell could be perceived as a snub to the government of Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha, particularly Public Health Minister Anutin Charnvirakul”.

Fuadi Pitsuwan, son of late former foreign minister and ASEAN secretary general Surin Pitsuwan, wrote that the move “highlights the royal frustration and the split among the ruling elites over how the Prayut government is handling the crisis” and was a clear sign of palace displeasure:

The royal move, exercised in this manner however well-intentioned, calls into question the political legitimacy of the government and its authority in the management of the crisis. It is a no-confidence censure and a royal rebuke of both Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha and Minister of Health Anutin Charnvirakul.

The Academy began large-scale imports of Sinopharm from China, and Chulabhorn started heavily promoting her generosity providing the vaccine — even though Thais have to pay for it and the palace won’t lose any money at all from the scheme.

The price of the vaccine was set at strange amounts that suggest royal astrologers were consulted — initially Thais were charged 888 baht, and now some doses are being offered for 777 baht.

Large banners at Chulabhorn Hospital and other Sinopharm inoculation centres use the same “royally bestowed vaccine” slogan and images of Chulabhorn feature heavily. The message is clear — this vaccine is a gift from the princess to the Thai people.

In a further humiliation for Anutin, he was summoned to kneel before Chulabhorn to ritually receive a fake box of Sinopharm. The symbolism could not have been more obvious — the palace was stepping in to do a job that the government had been failing to manage. Anutin had been unable to procure enough vaccine doses, so the royal family was intervening to save the day yet again.

According to Thai royal mythology, Chulabhorn is a world-famous scientist. In the late 1980s, her parents King Bhumibol and Queen Sirikit even tried to get King Carl Gustaf of Sweden to arrange a Nobel Prize for her, and according to Paul Handley in The King Never Smiles were “surprised and disappointed to be told that the Swedish king had no such power”.

In fact it’s not clear if Chulabhorn has any real scientific expertise at all, but she surrounds herself with some of the best and brightest in Thailand who do all the real work. Handley says that even for her graduate degree, “her research work and papers were handled by a team of palace-supported scientists”. Her high-profile intervention in Thai vaccine procurement was intended to show the superiority of royal wisdom and expertise over the incompetent efforts of government officials.

In any normal country, and any real constitutional monarchy, a princess intervening in vaccine policy in the middle of a pandemic without even coordinating with the government would be an extraordinary development. In Thailand, it’s just routine.

Thai royalists have never accepted the 1932 revolution that ended the absolute monarchy, and have never given up fighting to reverse it. A central part of this struggle involves relentless palace propaganda presenting the royal family as doing all the real work to develop the kingdom and solve its problems, in contrast to avaricious and incompetent politicians who just cause more problems and never achieve anything.

This was why Bhumibol and the royals made so many theatrical visits to remote villages over several decades, with the king scribbling on maps with his pencil and telling officials what needed to be done. This kind of ad hoc, amateurish and disorganised approach was no substitute for a real systematic national development strategy, but it reinforced the belief that Bhumibol was single-handedly toiling to improve the lives of his people while successive governments did nothing.

As historian Tongchai Winichakul wrote in his article Toppling Democracy, the king’s so-called royal projects were a crucial part of his mythmaking:

The truth about these projects, and their successes and failures, will probably remain unknown for years to come, given that public accountability and transparency for royal activities is unthinkable. Suffice it to say that the endlessly repeated images of the monarch travelling through remote areas, walking tirelessly along dirt roads, muddy paths and puddles, with maps, pens and a notebook in hand, a camera and sometimes a pair of binoculars around his neck, are common in the media, in public buildings and private homes. These images have captured the popular imagination during the past several decades. Bhumibol is portrayed as a popular king, a down-to-earth monarch who works tirelessly for his people and, we may say, has been in touch with his constituents for decades long before any politicians in the current generation began their career.

Bhumibol was portrayed as an expert in everything who had to chide politicians to get them to follow his wisdom. In the 1990s he started appearing on television lecturing officials on how to solve Bangkok’s perennial traffic problems. He had no expertise in the subject at all, but it reinforced the notion that only the king had the will and the wisdom to solve the issue. As Handley says in The King Never Smiles:

The average TV viewer got no information on the utility of his ideas, and even fewer understood that there was already a whole bureaucracy working on traffic problems, backed by international expertise. It appeared like only the king was confronting the problem.

Whenever Thailand faced a crisis or disaster — floods, droughts, cyclones — royal relief efforts were given endless publicity. It was never clear where the money came from — some of it was raised from donations but much of it was actually state funds, paid for with the taxes of the people. But it was presented as more evidence of royal benevolence, a gift from the king, with the role of the state minimised and ignored.

The promotion of Bhumibol and the modern Thai monarchy as the source of everything positive in Thailand was part of a broader narrative taught to generations of children which depicted the whole of Thai historical progress as the achievement of a succession of brilliant monarchs. In his study Thailand’s Hyper-Royalism: Its Past Success and Present Predicament, Thongchai observes:

Thai history is a collective hagiography of great kings who were leaders and exemplars in military, statecraft, diplomacy, trade, arts and literature. Many of them are celebrated as the “Fathers” of almost every aspect of the life of the nation. This history reinforces the belief that the making of the Thai nation is impossible without the monarchy.

The implication of all of this is that it was a terrible mistake to end the absolute monarchy in 1932 because this meant the palace now has to contend with useless and corrupt politicians to get anything done. It’s a compelling narrative for many Thais because of course a large number of politicians are indeed useless and corrupt, not least the current government. But it’s a toxic distortion of history that infantilises the Thai people and removes their agency.

Instead of being treated as citizens who deserve a competent government, Thais are taught they are subjects of a benevolent paternalistic monarchy and must be grateful to the palace for everything they receive. National development, disaster relief and even democracy itself are not something Thais have a right to expect — they are gifts from the royal family. The whole history of 1932 has been rewritten to claim King Prajadhipok himself graciously bestowed democracy upon the nation.

The attitude expected from Thais was satirised with the image of Khun Sapsueng, the symbol adopted by the legendary Same Sky web board where online debate about the monarchy began flourishing 15 years ago — an emoji weeping with gratitude for everything the monarchy had done.

Over the decades, the palace learned never to let a good crisis go to waste. It could always be exploited to boost the image of the monarchy and undermine the constitutional system of government. So it was inevitable that when the coronavirus pandemic threatened Thailand with catastrophe, the royals would seek to take advantage of it to bolster their exalted position.

But the problem for the monarchy is that Vajiralongkorn and his siblings and children are incapable of playing the same role as Bhumibol in promoting the mythology of a wise and paternalistic palace. Their efforts to exploit the pandemic for propaganda purposes began as comically inept, and later caused a disastrous policy decision that led directly to the kingdom’s current dire predicament.

II. Royal Benevolence Has Brought Great Joy and Appreciation to the People

On March 1, 2020, Thailand announced its first death from the coronavirus, a 35-year-old Thai man who worked in a King Power duty free shop. It was becoming clear that the pandemic was a global emergency and extreme measures had to be taken to contain it.

Defenders of the continued existence of royalty in the 21st century say a monarch can play a crucial role at a time of national crisis by uniting and reassuring the kingdom, and symbolically sharing their suffering. But Vajiralongkorn was nowhere to be seen. He wasn’t even in Thailand.

As his kingdom struggled with the gathering storm, Vajiralongkorn was five-and-a-half thousand miles away at the luxurious Grand Hotel Sonnenbichl in Bavaria, frolicking with a large harem of women, going on bicycle rides through the Alpine countryside, and doing his best to ignore the outside world.

Vajiralongkorn had been living in Germany since 2007, with brief trips to Thailand for essential rituals and ceremonies. This fact had never been officially revealed to Thais, but by 2020 it was common knowledge, partly thanks to work by Somsak Jeamteerasakul, Pavin Chachavalpongpun and me, amplified on social media which the regime was unable to censor. European media, and particularly the aggressive German tabloid BILD, were also starting to take an interest in the king’s antics. So his presence in Bavaria could no longer be kept hidden.

Vajiralongkorn had been widely despised in Thailand since the 1970s, but by 2020 he was hated more than ever, particularly after the Constitutional Court dissolved the progressive Future Forward Party on the orders of the palace on February 19. There was unprecedented criticism of the king on Twitter and Facebook, and at “flash mob” protests at universities and schools all over the country signs and banners openly mocked the monarch, something that had been previously unthinkable in Thailand.

There was anger and incredulity when it emerged that Vajiralongkorn had no intention of interrupting his 13-year taxpayer-funded holiday in Germany just because of a deadly pandemic. Bavaria announced an emergency lockdown on March 20, with hotels and restaurants closed, and residents only allowed to leave their homes for essential reasons. But instead of leaving Germany and heading back to Thailand, Vajiralongkorn’s servants applied for a special permit from the Bavarian authorities to remain at Sonnenbichl. It was granted, with the justification that the king and his entourage were “a single, homogenous group of people with no changes”.

In fact, however, Vajiralongkorn’s large entourage in Germany posed a significant risk of transmitting the disease. The king and his staff routinely ignored the strict lockdown rules, and several palace servants in Germany had already caught the virus.

In an effort to contain the outbreak, 119 staff were sent back to Bangkok on a Thai Airways flight on March 22. After arriving in Thailand on March 23 they were quarantined at various army hospitals in the capital. Nobody informed the German authorities that several members of the entourage who flew back to Thailand via Munich Airport showed symptoms of covid-19. Vajiralongkorn remained in Bavaria with a much smaller group of staff and servants.

Meanwhile, an unprecedented amount of information was being leaked by senior Thai sources who had become bitterly opposed to Vajiralongkorn. At the end of March I published a detailed article on the king’s lifestyle at the Grand Hotel Sonnenbichl, based on information from several senior insiders who confirmed that the king had a harem of around 20 women at the hotel. They had all been given a royally bestowed surname, Sirivajirabhakdi, and they were organised in a military-style unit which Vajiralongkorn called the SAS, in homage to Britain’s Special Air Service elite force.

Sources said Vajiralongkorn and the harem occupied the entire fourth floor of the hotel, including a special suite he called “the pleasure room”. Suthida, meanwhile, had been packed off to Switzerland where she was living a separate life at the Hotel Waldegg in Engelberg.

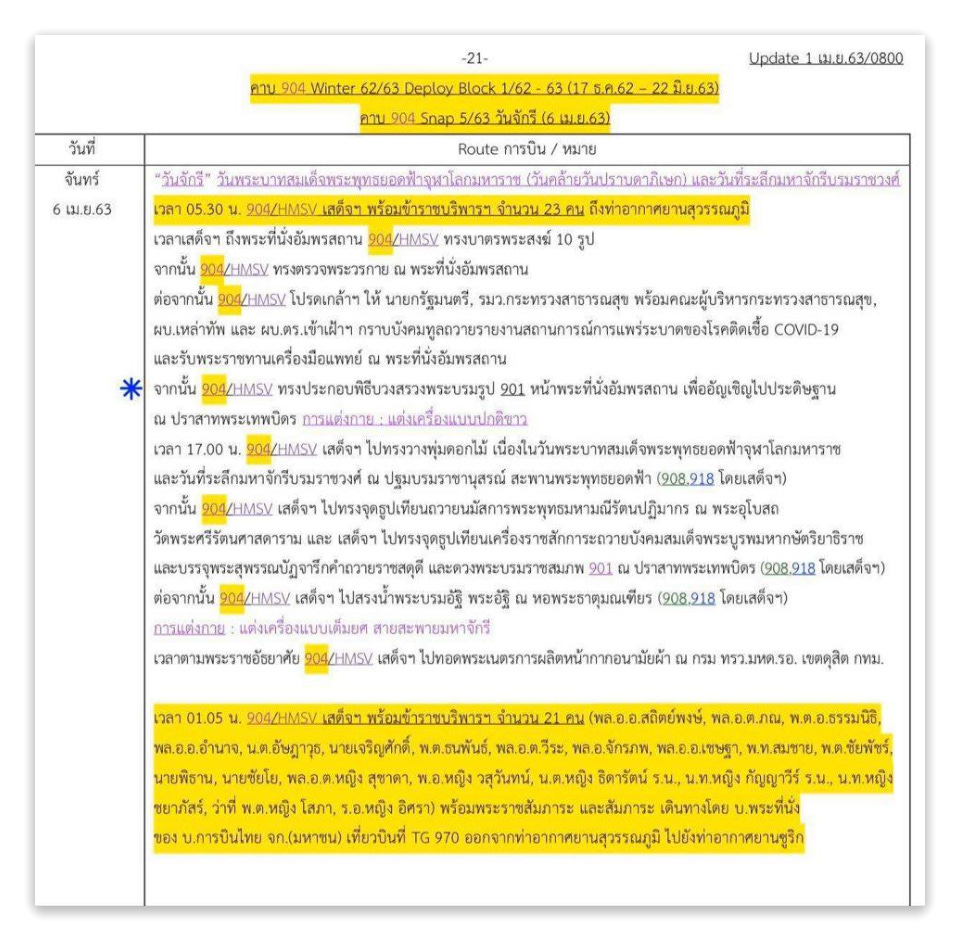

Vajiralongkorn and Suthida had been due to return to Thailand for a week in April, to mark Chakri Day and then the beginning of the Songkran holiday. But the government was forced to cancel Songkran events because of the pandemic, and in the end the king and queen made another visit of less than 24 hours, arriving early in the morning of April 6 and leaving during the night. In another sign of the resistance to Vajiralongkorn even within the palace, the schedule for the trip was leaked to me in advance.

By April 7, Vajiralongkorn and Suthida were back in Europe. The brief visit had required bankrupt national flag carrier Thai Airways to organise two return flights by a Boeing 777 from Bangkok to Zurich purely for the royal entourage. A photographer for BILD was arrested and handcuffed by Swiss police at Zurich Airport as he filmed the royal arrival from a public area.

Although the king and queen had spent less than a day in the kingdom, the palace desperately tried to pretend that the royal family was working hard and making generous donations to help those affected.

Bags of supplies, printed with large white letters declaring they were charity from the palace, were distributed to Bangkok slum residents by members of the royalist “Volunteer Spirit” organisation. Recipients were told to place a table or chair outside their front door, because the bags — which contained a small amount of rice, instant noodles, and soap — were holy royal artefacts which should not be allowed to touch the ground. Residents were also ordered to pose for photographs with portraits of the king.

In fact, the budget for the modest relief packages came from taxpayer funds, and the royal branding was purely for propaganda. Leaked footage of one incident showed Channel 3 royal correspondent Malinee Wanthong badgering an elderly couple to hold up a picture of the king and express their gratitude to the palace.

At the end of April, the palace released a video intended to highlight the generosity of the monarchy, entitled: “Royal Benevolence Has Brought Great Joy and Appreciation to the People.” They even added English-language subtitles. Recipients of royal relief supplies were filmed expressing their great joy and gratitude, but they looked scared and downtrodden rather than joyful and grateful. The video achieved North Korean levels of clumsy and ridiculous denial of reality.

The captions declared:

Their Majesties the King and Queen have graciously distributed relief supply bags in the capital to members of the public who are facing difficulties in life caused by the COVID-19 outbreak.

But of course, Vajiralongkorn and Suthida hadn’t personally distributed any supplies at all. They were far away at luxury hotels in Europe. One man, visibly shaking, said: “Their Majesties never forget their people.” But everybody knew that Vajiralongkorn had no interest in the welfare of the people, and he couldn’t even be bothered to spend time in Thailand as the country grappled with the pandemic.

Daily royal news broadcasts began regularly publicising donations of medical equipment and supplies supposedly made by the royals — ventilators, portable X-ray devices, mobile biosafety units, face masks, protective equipment. But as usual it wasn’t clear where the money had come from, or whether these donations had been coordinated with the government to ensure they were what was most needed, or were just handed out on an ad hoc basis. As with Bhumibol’s development trips in the Thai countryside, there was no sign of any coherent plan at all.

Meanwhile, the king’s youngest daughter Princess Sirivannavari was also trying to exploit the pandemic to boost her image and advertise her eponymous fashion brand. Copying the French luxury goods conglomerate LVMH, which had converted three of its perfume factories to produce hand sanitiser as the virus swept through Europe, the princess announced that her Sirivannavari couture company would also begin making the product.

But unlike LVMH, the Sirivannavari corporation had no perfume factories to convert. Instead, pharmacists at Chulalongkorn Hospital were ordered to produce the hand sanitiser, and the princess just provided the Sirivannavari branding and claimed the credit. The whole project was purely a marketing stunt.

To add insult to injury, Sirivannavari marked the launch of the sanitiser by releasing photographs on social media showing her dressed as a doctor with her favourite pet dog, the Yorkshire terrier Princess Perfume, wearing a nurse’s hat.

All over the world, the behaviour of the royals was generating embarrassing media coverage. German international broadcaster DeutscheWelle summed up the situation: “Thailand's king living in luxury quarantine while his country suffers.”

May 1 was the first wedding anniversary of Vajiralongkorn and his fourth wife Suthida, and to mark the occasion the palace released official photographs that showed the couple — wearing matching tracksuits — inspecting relief efforts at an army base.

Suthida was photographed sewing a face mask as her husband watched. The photographs were intended to give the impression that the king and queen were in Thailand and toiling to support efforts to combat the coronavirus.

In fact, they had spent less than 48 hours in the kingdom since the beginning of 2020, and the photographs had been hastily staged during their April 6 visit — as could be seen from the timestamp in the URLs of the images, which the palace forgot to remove.

Vajiralongkorn had been due to come back to Bangkok for the first anniversary of his coronation from May 4 to 6, and stay for Visakha Bucha Day on May 7 and the Royal Ploughing Ceremony on May 11. But with Thailand still in lockdown, the visit was cancelled.

On May 20, in an absurd ceremony attended by Prayut, army chief Apirat Kongsompong, police chief Chakthip Chaijinda and the government team handing the pandemic, the single face mask sewn by Suthida in April was handed over, and handled with great reverence as if it was some kind of holy artefact.

Four days later, Vajiralongkorn set off on a cycling trip in Bavaria accompanied by an entourage of around 20 people including at least one of his harem, and one of his pet white poodles. The strange scene was filmed by a bystander and the footage was given to BILD. The video showed the reality of the king’s life in Germany — far from working tirelessly to help Thailand overcome the pandemic, he was pedalling around the Bavarian countryside semi-naked with one of his concubines.

Inga kommentarer:

Skicka en kommentar