Andrij, 40, became the soldier's wife - now he is dead

Magnus Falkehed,

Niclas Hammarström (photo)

Published 2024-03-30 22.17

The buyer Andrij became the soldier Konan. Photo: Niclas Hammarström

I'm drinking my morning coffee when it pings in the encrypted chat: Konan, 40, the soldier who enabled Aftonbladet's reporting along the front line to Avdijvka in Ukraine the other week, is dead. So also several of his men.

It's happening again. And again.

The management of the dead; those who are dying, those who died and those who will soon die is one of the most difficult things to describe in the Ukrainian war.

Yet it is precisely this that, beyond the statistics, will decide the war.

As a reporter, I have never felt comfortable with the word "soldier".

Because Konan, whose real name was Andrij, should never have become a soldier. He was a husband and a father to a girl who is now studying in Prague.

His work had never been to kill fellow humans. It was to buy and sell grain to feed fellow humans all over the earth.

But like so many other Ukrainians, the Russian president forced him to put on a uniform and defend his country.

But since the buyer Andrij became the soldier Konan, he, like thousands of other Ukrainians at the front, had already been centimeters away from the ever-present death. The week before our meeting, he had driven a car that was targeted by a drone. His companion in the seat next to him died.

- Four out of twenty men under my command have died, he said then. At the time of writing, there are even more.

The news will never become official unless there is a public soldier's funeral. Then maybe a dark hearse drives slowly through a community somewhere far from the front. Flags flutter in the wind and people get down on one knee or just lower their heads a little to show respect and participation.

It happens in cases where there are bodies to bury. None of the missing bodies are included in any statistics of fallen soldiers in Ukraine. Ukraine. They remain missing.

People dying is something that has become commonplace in Ukraine, but that doesn't mean anyone has gotten used to it yet.

But people deal with fragility in different ways. Mobile phones are the main instrument in dealing with death. I noticed that already in the initial stage of the full-scale invasion in Donbass. Group photographs would be taken all the time.

- Do you remember the guy with the Stinger robot? He became meat-slams after we left, was one of the first messages my colleague Niclas Hammarström and I received in 2022. I picked up my phone and looked at the young, smiling and chatty man.

Same thing with roadblocks (with soldiers we joked about) turned into craters, buildings demolished with smiling waiters and customers in the throngs. The mobile phone goes up and the picture evidence that these people have actually existed for a time on earth is scrolled forward.

Out on the practice field, group photos are also taken. Then we're standing there a few months later with an acquaintance who points to the pictures: "he's dead and he, like him... You remember him too, don't you? He was the one who…”

I noticed a turning point about a year into the war, when the so-called meat grinder began to grind in earnest, mainly around Bachmut. Suddenly, more and more Ukrainians at the front felt uncomfortable with the question of what they would do in civilian life after the end of the war.

In fact, they only dreamed of surviving the night.

For the fortunes of war have turned—as if there had ever been any fortune in war?

Now the Ukrainian fighting morale is put to perhaps its toughest test since the start of the war of invasion. Wounded soldiers have to lie for hours and days waiting for help. New recruitment is at rock bottom.

Voters in Europe are preparing to vote for parties that want to end the costly aid, while Trump supporters withhold US supplies.

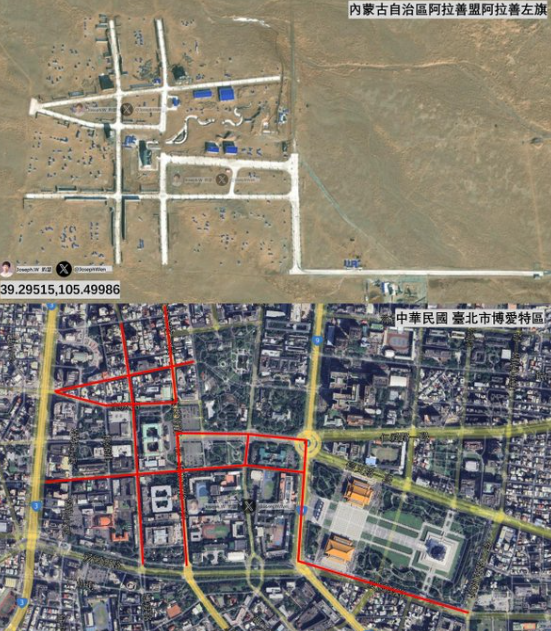

Russia lost tens of thousands of soldiers in Avdijvka – a small industrial town that can be closely compared to Swedish Grums. But in front of them, the Russians have a Ukrainian army that waited too long to switch to a defensive war.

Ukraine hoped that their friends in the West would indeed provide them with the necessary ammunition to drive wedges into the Russian meat grinder.

The four cannons Konan commanded were mostly silent. His Grad model rocket launcher was completely out of ammunition. The colleagues with grenade launchers 1500 meters from the Russians had only a few boxes of grenades, where they had previously been able to pour a sea of fire on the enemy who has now occupied their former trenches on the plain.

- I am the one who gave my soldiers the order to start digging new trenches. Excavators? No, they dig with their shovels, Konan told us.

Compare that to the lines of defense the Russians built with anti-tank concrete cones and acres upon acres of dense minefields before Ukraine's failed counteroffensive last year.

I asked Konan if he thought the Russians would soon capture the rail junction in the town of Pokrovsk, a good half-hour's drive on potholed roads northwest of his own position.

- The answer is simple. It depends on how many of us die. When we're all dead, the Russians won't be in Pokrovsk. Then they will be outside your capital, he said.

How it ends, Konan will never get to experience.